|

|

Wednesday, March 11, 2026

|

|

|

|

|

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEWS ABOUT THE BLOCK

2002

ROBERTA SYKES REMEMBERS MUM SHIRL [SHIRLEY SMITH]

Dr Roberta Sykes was born in the 1940s in Townsville and is one of Australia's best known activists for Aboriginal rights. She received both her master and doctorate of education at Harvard University, has been a consultant to the NSW Department of Corrective Services, including the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, and was the Chairperson of the Promotions Appeals Tribunal at the ABC.

Roberta Sykes is the author of several books, including Love Poems And Other Revolutionary Actions (1979) and Mumshirl (1981), Snake Cradle (1997) and Snake Dancing (1998) as well as having contributed to or co-authored numerous publications, journal articles, conference papers and screenplays.

I am about to interview Roberta Sykes about her experiences of The Block, particularly Mum Shirl and her work on The Block, her experience of people from The Block in the early days. Well, Roberta what are your dominant memories of The Block?

Roberta Sykes: Well I suppose The Block was all boarded up and lots of the houses there had been gutted and there weren’t facilities available. There were a lot of people around at the time who had nowhere to sleep and they would prise the boards off the windows and climb in and sleep there. [That was around] 1970, 1971, 1972.

Mum Shirl always had a concern for people who had nowhere to sleep and they would start sleeping in empty houses. She would run around to make sure they were all right. There are all sorts of background things that I am not sure about, like what triggered off the police oppression against the people who were sleeping in there, whether the developers suddenly got it in their minds. All those buildings belonged to somebody, somebody had been buying them, some big company, with the intention of developing them at some stage but years in the future. Meanwhile there was a shortage of shelter for people in the inner city so people were taking the advantage of going into the boarded buildings because they had nowhere else to go. Then the police started targeting that area to harass people and that’s when Mum Shirl and myself and others got involved. At the same time there were other targets of harassment like the Empress Hotel and places like that, where we understood the Riot Squad was being trained there by running in and rounding up blacks and things happening, and it seemed to us like the same thing was happening with people even less able to defend themselves.

They were just thrown into police paddy wagons, were they?

Roberta Sykes: Sometimes they were, sometimes they were beaten up. Then it almost turned into like a small urban war between the people and the police. Once we started to become involved, they started to get even heavier and they seemed to be, from my perspective, being trained to act without compassion. Since I would say the overwhelming majority of those young white male policeman had never known an Aboriginal, it wasn’t difficult for them to be made afraid of Aborigines, for them to believe all sorts of fantastic things about them, that they were crazy, their heads are as hard as bullets so you are going to have to bang them to get some sense into them, that sort of attitude.

So it was ignorance mixed with fear.

Roberta Sykes: Yes. All of that. In the middle of the night, we’d get calls and have to go down there. There were nuns involved and brothers involved from religious orders who came down and joined us. I remember one nun, whose name escapes me right at this moment, she used to come down and she was over eighty years old. I had to drive her home a couple of times and she used to get into trouble for getting home at three o’clock in the morning and being unwilling to say where she had been, because she knew that her superior at the convent wouldn’t approve of her activities. She wasn’t doing anything. You know she was running up and down the street trying to take down the numbers of police vehicles and the numbers of police officers. They are supposed to wear them on their collar but they take it off and put it in their pocket so they can’t be identified. She was writing them down. Identifying features if she could to show them the policemen who were most flagrantly law breaking. Because of Mum Shirl’s very close ties with the people in religious orders, she was the one who mobilised them.

She was probably living in the old church, the Redfern Church, or the presbytery next door? I know Father Ted has memories of her, but I don’t know whether it is that particular time.

Roberta Sykes: I think she moved in there later, I think the priest was still there at that time.

The former priest before Father Ted.

Roberta Sykes: I think the priest was still there. It was very early days. There were a couple of brothers from there who would come down, but I don’t think the priests actually did. They preferred to hear about it next day. The women were very, very involved. Most of the stuff that has ever happened has been led by women, mobilised by the women. Sometimes you have got a history of particular men who were involved in almost everything, but they weren’t [the] same sort of community organisers as, for

There was a Brother Tom.

Roberta Sykes: I know Brother Tom.

He was down the other day, still as passionate as ever.

Roberta Sykes: There were a few. There were a couple living over there at Manly that were involved. They had a house over there where from time to time they would shelter people.

Sister John too. She was there for a while. Maybe you don’t remember her. Sister John. She was Pat Durnham, but she was called Sister John. She is still around.

Roberta Sykes: I have a feeling she might have been after I was there.

She might have been. Father Ted wrote to many religious orders asking for volunteers to come up. I remember that because I was in Melbourne and I was rather keen.

Roberta Sykes: I don’t know that he was even there in the very early days.

You said there were other priests there.

Roberta Sykes: I remember I hitchhiked a ride up from Melbourne, coming up with what we called ‘The Holy Left’ coming up here for a conference and we got delayed because of thick fog on the road. We came up via that inland road, and we didn’t get into Sydney until about nearly three o’clock or something. They had agreed to previously to drop me at my sister’s place in Gladesville but we got in too late and they said, “You’ll have to stay at the presbytery.” The presbytery had been left open for them. Four of them had come up for this conference, but one old priest who was there had got up and gone for a walk and come back and closed the door. So they were locked out and nobody slept on the ground floor and they were unable to make anybody hear. A little transom, a little window was open and they tossed me up and I scrambled through the window. They were really wary about doing that because they thought if the police go by and see four white blokes shoving a black woman through the window, they’d think we were trying to break in or something, we could end up arrested or worse. Anyhow I came round and opened the door, they all filed in and went where they were going and they put me in the lounge room on the ground floor. I was very tired and they had this big leather furniture, big leather chairs, and I woke up in the morning and I realised someone had opened the door and closed it again and when I looked, there was nobody there but it was enough to wake me. So I got up and I walked out the back and there was a long, long table there with all these priests that I didn’t even know. A very old head of the presbytery, or whatever, blessed himself because he slept under the same roof as a woman. (Laughter) He must have thought he had committed a sin. It was really quite funny. There weren’t any women there and I was led to believe that I must have been virtually the first one woman to have ever slept in the presbytery.

More came later I think. So you were living in Melbourne then?

Roberta Sykes: I was more or less in hiding in Melbourne.

I don’t see, but I understand.

Roberta Sykes: I was doing work with Nation Review and I didn’t have any fixed abode.

You were an activist, weren’t you?

Roberta Sykes: So I knew Mum Shirl through all this time. I just know so much about her and her many activities. It is very difficult for me to parcel out that little area of The Block. All these other things were connected with it because a lot of the people were on The Block, in prisons, or she would help then when they were being evicted [or] go to court on their behalf. She was always concerned about their lives. So it is in the context of those things that The Block occurred rather than The Block stands by itself. I think that needs to be made clear, because otherwise we might think why should she be involved in that. It wasn’t that she wasn’t involved in The Block but she would have been involved in any area where people weren’t even allowed to put their head down and rest. She was also very actively involved in the old building that became the Black Theatre. It is all interconnected, interwoven as people were driven from one place to another. It was like The Block became a last stand for some people.

People had great expectations after the election and the Labor government started looking as if they would actually buy The Block for the people. People started to dream about this as an area where people could live without being molested. I went with Mum Shirl to a police conference. She’d asked the police for a conference and they had agreed because the newspapers were picking up about the violence that the police were perpetrating against the black community on The Block. Then, whilst they agreed to a meeting and Mum Shirl said, “You must come to this police meeting,” they delayed the meeting for so long, so long that when we got to the meeting we started to talk about the complaints, they said, “That was months ago. Have you got anything recent?” That was the whole tenor of the meeting, they controlled it. In my own way I thought this was a complete waste of time, but Mum Shirl never thought anything was a waste of time. You know, she would have waited for five years and she would have recited the list of abuses that had occurred just to refresh their minds. But their minds didn’t need refreshing, they knew what sort of things had been going on and they had pulled the police back for that period of time to create [a significant period of time] between when it [police abuse] occurred and when a meeting would be held.

This is very important because no one else has mentioned that sort of thing. None of the other people that I’ve interviewed or others have interviewed have actually mentioned that, so it is very good to hear this aspect of it.

Roberta Sykes: I can’t recall who else was at the meeting. I know there was me and Mum Shirl but I just can’t recall right now, if I thought about it for a day or so I’d probably remember, the names of all the people who were there, there weren’t many of us. We were of course outnumbered by the police who turned up, all senior officers, some of them smirking behind their hand. Unfortunately, Mum Shirl from time to time, because of her paucity of education, used words inappropriately and if she did that they would smirk, you know. Yet at the same time, well increasingly over time, whenever there were riots in prisons, who did they send for? Mum Shirl. Mum Shirl could walk into a rioting prison and go “STOP THAT,” and they knew that she could do it. They never paid her for this. They would pay for a taxi to take [her] to and from prisons in Bathurst and Goulburn. A taxi driver would take Mum Shirl. I have written about this previously too because I was so appalled.

Their respect for Mum Shirl certainly grew.

Mum Shirl was a figure that they held in awe. They never regarded her as a human person who had needs. I mean it was people like myself that she was always borrowing money off to pay rent or to pay the electricity bill. I mean I would go there and the electricity would be cut off. At the time, I was a single mother supporting two kids so it really was very difficult for me to spare money to give to Mum Shirl even for her own personal needs. A great deal of the time, it wasn’t for her personal needs. She’d come to me with some sad story about how somebody was being evicted and she had got five kids, dee dah, dee dah, dee dah, and hadn’t been able to pay the rent. It seemed to me that if I put the money up for that, then in three months time I’d have to do it again, the situation wouldn’t improve and the need would just pop up again from time to time. So I tried to restrict my financial support of Mum Shirl to Mum Shirl’s personal situation because I didn’t want to find her sleeping at a bus stop. I mean it got that close so many times.

What role did the South Sydney Council play in all this building? You said that the housing was owned by somebody. I know Ted had some tussles with the South Sydney Council later on.

Roberta Sykes: It was around that time, but which came first I am never quite sure. It was around that time that the South Sydney Council were harassing the Aboriginal Medical Service. I was writing a newsletter for the Aboriginal Medical Service and there is a litany of obstruction by the South Sydney Council. They said, “If you put a medical service here, it will attract Aborigines to the area.” As if you could overlook the twenty thousand that lived there, which of course they could and did. I don’t recall any active opposition in relation to The Block in particular, but that is not to say that there wouldn’t have been, I wouldn’t know. At the same time I was writing for Nation Review so I was trying to maintain a national focus rather than just concentrate on The Block at any given time. There were episodes with the police and people there at various times that I couldn’t even get to.

I was going to ask you about any particular personalities that you remember at that time who had to do with Redfern and The Block.

Roberta Sykes: Well there were a number of people. I just can’t remember anybody being there consistently, all the time, but there were people like Gary Williams.

Was Gary Foley around at that time?

Roberta Sykes: He was certainly around. There were a number of people around. He was around. I don’t want to put him into any particular situation he might not have been in. He was around, he was busy, he was active, he was there. If he was there, it was probably on nights when I wasn’t there. I mean this was night work, virtually every night.

You were monitoring the police mostly at that time?

Roberta Sykes: That is one way of putting it. We were there to see what the police did and do whatever we could about it. I mean various of the religious people, and Brother Tom might have been one of them, went in and sat in the houses. A couple of the religious people were arrested in the houses. By that time it was no longer a matter of prising the boards off the windows. You could walk through the doors. But there wasn’t anything there and the police could come and arrest people. They arrested one man for sitting on the toilet and they said he was loitering with intent or something, a ridiculous, ludicrous charge. Another man was sleeping on a bit of blanket on the floor, and he was drunk and disorderly in his bed.

These were empty houses, weren’t they?

Yes. In order to stop people using them, they had disconnected the toilet facilities and smashed the cisterns and all that sort of stuff. Ripped the electricity out. Ripped holes in the floor to discourage people from using them. So people would jump over the holes in the floor to get further out the back where they had to flee from the police. I mean we all got to wander through the houses and those of us unlucky enough to be there when the police arrived would be arrested for being there. The brothers would come and sit on the floor so the police had no option but to arrest them as they arrested the Aboriginal people too. That was interesting. I mean it wasn’t like burning the Christians, it wasn’t that gigantic, but it was very pleasing to me to see the level of commitment of some individuals. I can’t generalise that across the whole church because there was opposition to what they were doing from inside the church.

Is there anything else you’d like to say particularly, about perhaps your personal reactions or the effect it had upon you personally, this experience.

Roberta Sykes: What, The Block, Mum Shirl? Mum Shirl had an enormous impact on me over time, not specifically around The Block but around everything. Everything was of a piece for her. It wasn’t that there were mountains. It was all the same fabric as far she was concerned. Her ability to mobilise people. I mean Mum Shirl herself couldn’t have stopped the force of the oppression by the police in that area, but she was certainly able to mobilise lawyers, mobilise priests and brothers and individuals such as myself. She would phone me and I would have to take her or meet her there. It just seemed to me that her ability to mobilise women was very important. I think there are a multiplicity of reasons why women were largely involved, but one of them is that Mum Shirl was so into what the men’s business was because she was almost regarded as asexual. Where various others of us couldn’t have trodden with the safety that she did. Most of that people who were sleeping in that place were men. It wasn’t as if we were protecting a whole lot of women who were in there, the people who were in that situation were men, the overwhelming majority of them. When they started to get really into trouble, Mum Shirl mobilised a whole lot of women around them, if that makes sense. Interspersed with those women were a whole lot of religious people, some of whom were women but some of whom were younger men. The women who came were older, the brothers who came were much younger, they had sort of radical priests, I suppose, radical brothers inside the priesthood.

It was a very radical time wasn’t it, the 1960s, the 1970s. It was in the church anyway. The doors were open, the windows were open and there was a greater freedom. Or if there wasn’t actually freedom given it was easily taken.

Roberta Sykes: A time of rapid change. I mean nuns started to wear things other than habits. I remember when I was growing up as a girl that could never have happened. I used to talk to one nun in Townsville and she used to talk about the inappropriateness for the tropical climate. She also used to want to ride on a motor bike. She knew she would die and never go for a ride on a motor bike. She had seen a picture of nuns in other countries on scooters, those little scooters. She had seen pictures of these nuns on scooters but it was a very oppressive environment in the convents at the time.

Yes I think so. There were changes on the horizon and some people had sensed the wind of change.

Roberta Sykes: Didn’t reach far north Queensland. I mean I didn’t see television until I was older. [Laughter]

So you were educated by the nuns were you?

Roberta Sykes: Yes. I wasn’t a boarder, but I would say I lived under their auspices or aegis at times and I left there very bitter about them, very bitter about them.

Because of what?

Roberta Sykes: Because mainly of their racism, their autocratic decisions in relation to the lives of the people who they are supposed to be tending, the flock where they weren’t supposed to see black or white. They certainly had my life cut out for me and it was a very tiny life with a small future at the same time, they could congratulate themselves for having taught me to read and write, as long as I didn’t want to read and write anything analytical. Anything like that, I had delusions of grandeur. That sort of stuff. I wanted to do physics and chemistry and they said, I had to do domestic science. Only one teacher there took me seriously, Sister Sebastian. They created a schedule for me. I said I didn’t want to do the domestic science and they said, “You’ve got to do domestic science, but we won’t make you do the whole thing, you can do typing and Pitman’s shorthand.” Of course that left no time for me to do anything else that I would have loved to do. Sister Sebastian used to meet me at school at about seven or eight o’clock in the morning so I could have an hour in the lab.

What a wonderful woman.

Roberta Sykes: She was.

You would have been an independent person wouldn’t you, a pretty independent young person and that wasn’t approved of often.

Roberta Sykes: I didn’t feel that way. Even now I don’t compare myself in relation to this one I’m radical, to this one, I’m not. I mean it is just inside yourself. Whether or not I was independent or not is an external observation rather than mine. I think there were just things in my mind that I would have liked to do, and a direction I would have liked my life to take, and I was thwarted from doing that. I had to go into a different direction and be more opportunistic rather than that I could make a plan. I really wanted to do medicine at school but the idea of a black person doing medicine in 1940 in Queensland - no way, you were just stopped dead.

How did you become involved in activism, how did you become an activist?

Roberta Sykes: I don’t recall that I ever started. I recall when I was walking home from school and people were throwing stones at my sisters I would tell my sisters to run ahead and I would fight them off. Is that activism? Well in that case, I started when I was nine.

You were able to plan strategies against aggressors.

Roberta Sykes: I plan strategies and defend others. There is a story in my family about my sister wandering home and my mother saying, “Where is Roberta,” and she said, “She is in stone fight.” My mother said, “Why aren’t you there helping her?” and she said, “She’s winning.” The expectation always was that because I was the oldest I would fight the battles for my family and I suppose you just extrapolate and there isn’t a point where you think you are going to be an activist or a radical or something like that. If you see injustice and you do nothing, I just can’t imagine such a situation where I feel I can do something, that I can do something about, and I don’t. The people in the kitchen will tell you I was round there at McDonald’s the other week on our way home and there were four white guys there who I think were journalists, or work in a newspaper, and they were there in their suits and one of them threw their garbage at this sleeping person.

Was it a white person?

Roberta Sykes: Yes. Or Asian. This person was sleeping there. Had very short hair and I thought it was a man but they tell me it was a lady they let sleep there for safety. I looked at this man and said “What do you think you are doing?” I went up to the manager and I said, “You are the manager. How can you be letting this happen?” He said, “I didn’t see it.” One of his staff came up and said, “I saw it.” I think for a moment he would have liked to think I was making it up. I said, “Those blokes are throwing stuff at that woman.” Wasn’t long, the white blokes ran out of the place. They weren’t going to sit there any more. It was none of my business.

In one sense I think it is all of our business.

Roberta Sykes: The place was full of people and they never said anything. It doesn’t bother me. I can’t go home and sleep. I seem to have that, and it is not something that I wish, something I desire --- a stronger sense of conscience. If I was to walk past somebody being assaulted and do nothing, I would feel very, very bad, it would play on my mind for days. I can’t imagine that I would do it. If I could do nothing then I would run and find a phone and phone the police. That is what bothers me is that if I have this conscience that comes right out of your organised religion, imagine the people who are in an organised religion not have it?

That’s a good question, that’s a very good question.

Roberta Sykes: They are supposed to hold themselves up to be involved in human rights and spiritual rights and that sort of stuff.

They shouldn’t be separate actually. Human rights should be part of religion, or spirituality anyway. Human rights is really religion, is spirituality if you go back to the Gospel.

Roberta Sykes: I would think so. The Gospel admonishes people to be kind. But I don’t think that is the word they must use, because I don’t do these things out of a sense of kindness, a sense of 'I am better than them' ...and I will therefore save them. It is not ‘them’. There is no ‘them’. The ‘them and us’ [is what] other people create, but in my sense, I don’t care who is being assaulted in the street. I don’t think [for example] 'that is a white person', so I won’t worry. It just doesn’t occur to me. That is not to say that I’m colour blind because there is so much racism directed against me all the time. I am very, very aware of racism in other people.

In your own history and experience too. That is probably why you’ve got this acute sense of justice that other people don’t have, church people don’t have. I am just guessing here.

Roberta Sykes: Mum Shirl had an enormous sense of justice although she didn’t always know how to verbal injustices when they occurred and she didn’t know why they occurred. She wasn’t an extremely analytical person. She acted more out of heart than head.

Can you remember a particular incident in which she was involved?

Roberta Sykes: On The Block. There were hundreds, she had her finger in everything.

I know her brother was gaoled, wasn’t he? Laurie. That set her going, didn’t it?

Roberta Sykes: The ‘Black Bat’. He was gaoled as a younger man for things that he did. In the end, he was gaoled for a murder that he didn’t commit. That really pulled the soul out of Mum Shirl. She was never the same person.

He died soon after he was released, didn’t he?

Roberta Sykes: While he was in gaol, he had a stroke that centred on the speech centre of his brain which meant that he was unable to talk. When they went to court and it was thrown out, after he’d been sentenced, they said this should never have occurred, they shifted him in the same hospital from the prison section to the ordinary wards. That was it, that was his freedom. He came out but he never recovered. He recovered little words, but not like the power of speech.

How long did he survive after that?

Roberta Sykes: I’m not sure because that was about the time that I was in America. That was happening just before I went to Melbourne and in fact I don’t think I was here for the trial. I can only think the reason I didn’t go was because I wasn’t here. Otherwise if I didn’t personally set foot in the court, I would have to drive Mum Shirl backwards and forwards every day seeing she didn’t drive and she was able to get around on public transport.

So Mum Shirl dedicated her life to fighting injustice within the communities.

Roberta Sykes: Well I would say Mum Shirl was looking for justice rather than fighting injustice. There is a difference.

Yes, there is a difference.

Roberta Sykes: She was never real keen on the physical aspects of having to fight for something. She was very reluctant when we had the embassy in Canberra. She was very reluctant but she did put a brick in her handbag. Otherwise she could pass herself of as a little old lady but the police up there weren’t interested in differentiating between [the] little old ladies fighting for blacks [and ordinary citizens] so she thought she had better defend herself and she put a brick in her handbag. A big handbag she used to have. She would always have to say prayers, she felt so guilty.

She was MRC.

Roberta Sykes: Mad Roman Catholic. Yes. She was a person who gave me great inspiration and provided an example. At various times I thought I would willingly trade some of the things I have for some of the things she has, because I would often be in enormous conflict over some of the issues that she saw no conflict about. I mean she would help all those people who were chronically being evicted every three months, I would see that as money going down the drain.

Why did you see that as money going down the drain?

Roberta Sykes: Because it is not going to solve anything. Over and over and over, the people don’t learn anything except they learn they can depend on you to bail them out over and over and over. Where I think you’ve got to break that cycle. They then become dependent upon you and you’ve got to break that cycle of dependence in one way or another and you have to encourage people to empower themselves rather than… If you get caught up in a system you can be contributing towards crippling somebody. Mum Shirl just saw the victim. She saw the family being put out on the street, that sort of stuff. She had foreseen it many times so she wanted to prevent that, but I am not sure the way of preventing it is going and getting money off of other people, paying out this time and leave it there until it arises again.

I know what you mean. It requires a lot of hard discernment.

Roberta Sykes: Mum Shirl didn’t have the capacity to say no. She did other things but she got overwhelmed, which she did. She often used to come to my place and hide there for two or three days where nobody could find her. “If anybody rings, I’m not here.” “Why would anybody ring? Did you tell them you were coming?” Mostly the people who would call on her for help would walk round to her house or they’d phone up. I have always had an unlisted phone number so she just found it was a haven, it was too far for anybody to walk. Across the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

That was convenient.

Roberta Sykes: Just across the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Crows Nest. People who live in Redfern they won’t cross the Sydney Harbour Bridge. It is almost like there is a big wall, an invisible wall. There are a lot of places around the inner city too where Aboriginal people will not go in. There is not a sign up saying, ‘No Aborigines’, and they won’t be insulted, but there is a poverty mentality that that place is too good for them.

Colin James wrote an article on the Block, didn’t he?

Roberta Sykes: He was an architect. He wrote a report. I also I have written a report about the gentrification of Redfern that Lili knows about. I mean there is enough written stuff but she just wanted to know if, on reflection, I had changed my mind, why I had changed my mind. I have had a lot of problems with the way the Block has developed now.

The Block, like any other Aboriginal projects, was set up to fail. Because no sooner had the government bought it, than the newspapers were advertising all over Australia ‘Housing for Aboriginals’ Thousands of people have come from as far away as Perth and North Queensland. We were never going to be able to accommodate the number of people who were then involved in the influx and there were a whole lot of people there who couldn’t say no, and so people were sleeping on broken down floors and it was unhygienic, they were without toilets. The ‘rellies’ [relatives] started flowing in and there was an enormous number of people there. I don’t know, I wasn’t there, but there must have been conflict about the people who would hang on the longest and get the houses. I would say different ones from Western Australia would be very much on the outer and told to go back to where they came from. I mean it was a disservice by the media in the way they portrayed the purchase of that block. It started off being overcrowded, under-resourced and then people had no experience. Even when they started to get up and go, you will notice all the floors in there are softwood, not hardwood, they aren’t very strong and the rats come up between the boards because it is softwood. They had no experience to say to the people who were doing the building that they wanted hardwood floors. Those sorts of things. At the same time they were trying to seize for themselves the overseeing of the site - [a] role for which they were [not] educated or prepared. People like Colin James could have told them that - they didn’t want a white person. He is not intrusive. Some of the people who were involved then were rip-off merchants, various ones who were involved in the construction were finding cheap materials. Only somebody who is experienced could say the difference between a floor and a floor, and a wall and a wall. It was never set up to be permanent. There was a transient quality about the quality of the housing.

Very interesting in the light of what has happened. There are plans to rebuild the Block once more.

Roberta Sykes: I hope people have learned. Hopefully we will have some structural engineers of our own. But [that] doesn’t mean to say they are good. It doesn’t mean to say that they are committed to the development of the black community, unfortunately, just because you have an Aboriginal structural engineer.

Would you say that education, in some cases anyway, seems to divorce Aboriginal people from doing things in their own communities, perhaps from where they came from, and they go on and naturally, [they] want to perfect themselves in their career, but they perhaps don’t see that helping their own community --- which could be a run-down community, they are not interested any more?

Roberta Sykes: Well it depends. That is an accusation that has been levelled at me because I don’t really do much for Townsville. [Laughter] One of the problems is that when you develop national perspective, then in a way patronising your own community could be seen as nepotism. So you have got all these conflicts you are juggling up and down all the time. If you are just talking about the development of technical skills, is that what we want? Not necessarily. Once you start talking about broader education, seeing the problems of your community in the context of the national picture, then you raise that person’s perspective up to a national level which makes it difficult for them to patronise from there. But the development of technical skills, how it affects trucks or something like that, that doesn’t necessarily involve the same problems. Send them out, teach them to become a mechanic, bring them back, teach them how to do electrical wiring and bring them back. But the wider question of why there has never been power, if they start to nibble on that, then they could develop a problem of a national perspective.

Then they become role models too, many.

Roberta Sykes: If you say, “I am going back to my own community to do this or that,” “ but you are a hundred miles away [and] you know there is a community in worse trouble, what do you do? You have got to [confront] all these forces [that are] to-ing and fro-ing with you all the time and think it becomes very difficult for people whichever way they go. They are going to be accused of either abandoning the national picture or something like that. It is problematic and it requires a great deal of understanding beyond the level that I think is available in the community generally. Those people who do, like Louisa Beresford…

She is writing this book, you know that, don’t you? Well, editing...

That doesn’t surprise me. Well I hope she is doing those sorts of things. I spent a great deal of money on her education.

Congratulations. So this is what you are doing. She is coming back now and she is contributing to that.

Roberta Sykes: Well so she should. I don’t have to tell her, she would be aware that they were my expectations, but at the same time, I don’t want her just to sit down and write a book about the Block when she actually has this international perspective for which I have paid a great deal of money. She races off to Canada and Whoop Whoop and gives these speeches and stuff like that, and so she should. At the same time she is able to keep that finger on the pulse of that local community, and that is good too.

That’s good too. The book will be valuable too, historically; it will be very valuable if it is done sensitively.

Roberta Sykes: Yes although whether it will do anything for any of these problems in Redfern,

I don’t know. Although sometimes I get surprised. I was walking down near the station one day, you know, the traffic lights, TNT Building? A group of black women from the Block came around the corner and one of them yelled out to me. [Laughter] I thought, 'when you think of the Block, it is not as if the people out there will be able to read it'.

The level of education is rising, even on the Block. I don’t know. We have quite a few books and when people ask to read them, I don’t hesitate in saying 'yes'.

Roberta Sykes: I know those two girls, one is a drug addict one is a university student. Her sister was at university. She had opportunities but she hit the needle and her lifestyle was chosen. They were living in the same house, one was dealing and the other one was at university.

It is crazy. The contrasts on the Block are amazing.

Roberta Sykes: You are hard-pressed to find a family down there that is not. Everybody is impacted by drugs one way or another. Far too many people benefit from the drugs, even though they may not deal in them, in crisis they will turn to a dealer and he will give them money and that will sedate the lot of them. When I say it is a danger, I don’t mean the drugs, I mean the monetary solution to something. I mean there are people down there driving brand new cars and they don’t have a tax file number. There is all this infrastructure around the city, these white folk who will sell them a car for cash. I mean you go and buy a $50,000 car for cash, a big suitcase.

The people are very, very intelligent and clever. One of the things that I feel is that there is so much hidden talent all around us there.

Roberta Sykes: If only it could be pointed in the right direction. So many people who are turning their talents to criminal pursuits or the pursuit of money. I wonder if they ever reach a point when they regret it.

I think some of them do. Some of the people kick the habit.

Roberta Sykes: Not even the addiction, but the sense of waste. I mean there are a lot of wasted people down there who have never taken drugs.

Exactly. They have got themselves into a hole and they can’t get out. Or they won’t or they feel they can’t. Well thank you so much.

Roberta Sykes: I am sorry I don’t have better news. In a way [the Block] is like a forest that has been ravaged by fire. Have you seen those little green shoots coming out after the fire. It will take time. But while ever there are new shoots, [while] there’s a little green shoot there...the possibility of transformation of the area continues to exist. It is when we all turn our back on it that it will become a mire with no little green shoots in it at all.

Well, thanks a lot.

Interviewer: Sr Pat Ormesher

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

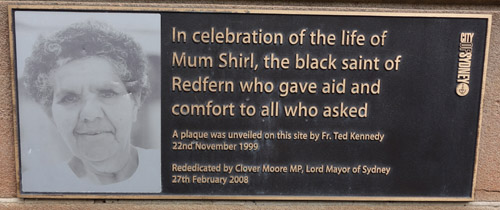

Mum Shirl memorial rededication

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Terms Of Use

|

Privacy Statement

|

Copyright (c) 2026 Redfern Oral History

|

Register

|

Login |

Website Solution: Pixel Alchemy

|

|