Vicki Grieves interviews Adam Hill political artist, visionary and critic of Australian whiteness

© all rights reserved

True art is spoken / performed, viewed / witnessed with the heart. If you are not communicating something surrender your space, as it is valuable beyond measure.

True art is spoken / performed, viewed / witnessed with the heart. If you are not communicating something surrender your space, as it is valuable beyond measure.

– Adam Hill

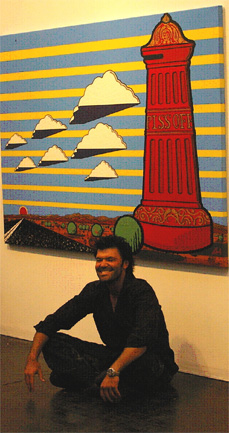

The exhibition “A SIGN OF THE CRIMES” that was held at the Mori Gallery in Sydney in May 2006 proved a splendid confrontation of Australian whiteness and the impact of continuing colonial oppression of Australia’s Indigenous people. The Indigenous artist Adam Hill is an exemplar of the urban black: his early years in the outer western suburbs of Sydney led him to a developed political consciousness and deep understanding of the dynamics of Australian society around race, class and whiteness. This political and social consciousness is reflected in his art. I had a conversation with Adam Hill about the development of his indigenous identity, his life experiences, his art and the role of ‘whiteness’ within it.

Being Indigenous

Vicki Grieves: Adam, your art has obviously grown out of his life experience as an Indigenous person. Where are you from?

Adam Hill: Penrith. Born in Blacktown , grew up in Penrith. Did all my schooling through to university, to a Graphic Design degree, and Penrith is my stomping ground. My mob is from Kempsey; my grandmother was a Morthem from Kempsey. Big mob in the early days up there, in the ’50s, and there’s still Morthems, but then they turned into Drews, and Silvas, Ridgeways and Donovans. Dainggatti country.

VG: Yes, my family’s from a little further south. Foster-Tuncurry. I’m Worimi. I’ve known a lot of Daingatti people over the years, I’m related in. Very nice country too. So it’s a small world, isn’t it?

AH: Koori world’s a small world.

VG: When you’re Koori yeah.

AH: So my dad’s blackfella and my mum’s whitefella, and the whitefella side of the family I grew up with really because dad was somewhat separated from his mob when his mother died. She died when he was only ten years old, and his father was white, and his father was off to war, see. And what prevented dad from being institutionalised like everybody else of mixed heritage at the time was that he had white relatives. He grew up as a whitefella basically, and it had an astounding affect on an Indigenous man.

And, so, what I became interested in was that I didn’t know anything about our people and I lived with a father who was black, and we started to study it at school, and kids would say “Hey, your dad’s Aboriginal.” And then ask me questions, and I didn’t know what. I just grew up in a blue-collar working class suburb with all the other mixed and working class mob. There were loads of different people, from various ethnic backgrounds, but there were only a handful of Aboriginal families in our neighbourhood.

Anyway, so then I went to university, down the track, and to the Aboriginal Unit at the University of Western Sydney . They, the first question they asked was where were my mob from, and I kept hearing this all the time and didn’t know. So I went back, and finally sat down with dad at the age of twenty-six and said “Where do you come from?” and “Where’s our Mob from?” So he pulled out all these amazing photographs of my, of the old people from Kempsey. And that brought me to my Indigenousness.

Being an Indigenous artist

VG: How did you begin to be an artist?

AH: It’s something that just happened in my life. In fact, I grew up watching my uncle that’s on my mother’s side of my family who was very artistic and I had a great uncle who did some work at the Australian War Memorial. He was just the most brilliant artist I knew, so growing up watching those men produce that kind of work was deadly.

But what happened was, I was studying design, graduating at University of Western Sydney , then I went to, the first job out of university, I went to a big contract with the Australian Museum to assist on the design of the Indigenous Australian exhibition. Which, during that eighteen months that I was working there, I met all manner of different mob from all over the continent, and I started to see “Man, these people look nothing like my people, and these people look nothing like those people.” And I started to realise how different it all was, and the fascination continued.

Actually it all began with playing didjeridu , because it’s commonly perceived that you play didjeridu if you’re an Aboriginal boy. So, through my exposure to a donateddidjeridu from Yothu Yindi, for the exhibition, I developed a fascination for it, like a lot of other people.

I was twenty-eight by this stage, because I was just fresh out of university, and that’s when I decided to start playing the instrument, and that. The whole learning curve began with the instrument, because that took me back to the homeland, the origins of the instrument, which is North East Arnhem Land. I have close friends that I visit every other year. Yolngu people. So I went up there to learn about it, and came back with information, the correct information on the instrument. So what was exciting was that it was just one cultural item belonging to one people – so that was the Yolngu people from North East Arnhem Land – and when I came back here my mind went berserk, and I just realised how much there is to learn from different people, starting with my own.

So back to Kempsey I went, to Aunty Edna Dotti, she’s passed on now, and I tried to find out who knew my grandmother, and got some little bits of information and started hanging out a bit in Kempsey. Get a bit of spirit into me from there, and came back to Sydney . Of course, you go away, you escape Sydney and everything that’s wrong in Sydney , and after you come back, after you’ve had time to rejuvenate your spirit, and you come back and everything compounds.

And I found that, you know, you look around and see them in their own country, and start to realise how much people still take Indigenous people for a ride, so to speak. And just how much money is boldly thrown around in Sydney , and New South Wales , being the richest state in Australia . Then things started to come back to me. Because I’ve seen the beauty, the structure of remote communities and remote culture, and then coming back here and realising that’s what our people used to be like. That’s what the people of Sydney used to be like. But we continue to disrespect Indigenous people en masse. So that’s how my heart began to flow, the juices, began to feel what I paint about.

Being urban

It’s taken a long time for that appreciation (of Aboriginal art) to be focused on urban Aboriginal artists because we’re a hostile bunch. We’ve got things to say and people have been too scared to confront that. My current series of paintings are really quite in-your-face. There are a lot of other modern urban Aboriginal artists who say this confronting stuff and it’s now becoming collectable, so it’s inspirational to see these people reach success in the art world. Whitefellas in the art society are becoming interested in seeing these controversial messages and that’s exciting.

– Adam Hill

Deadly Vibe Issue 84 February 2004

VG: Yes. Well the inner city is quite a haven though for Aboriginal people. Do you think it’s a kind of a refuge?

AH: Yeah, inner city?

VG: Yeah, because there’s so much acceptance, in a sense, of your difference as an Indigenous person in the inner city.

AH: Oh, are you talking Redfern?

VG: Well, I live in Redfern, yeah. But generally speaking the political climate’s quite different, the inner city electorate for example are much more sympathetic to Indigenous issues, than you find in rural electorates, country towns.

AH: Yeah. Well, one would hope. One would hope, but we still find it problematic with what’s happening on the block, and the redevelopment of the block. It’s a very slow and somewhat sneaky cleansing of the area.

VG: And it’s kind of, it’s like a juggernaut really, you can’t see how it could possibly be stopped.

AH: No, you can’t see how it could possibly be stopped, and when you think you have certain people on your side, and then ultimately the dollar quickly reigns supreme, then you start to realise, and you start to become just a tad more heartbroken that you’ve been let down once again.

The thing to monitor there is just how much control the Aboriginal Housing Company has on what was promised to them in terms of the ‘x’ amount of residents being distributed to Indigenous housing, so it would be very interesting. A very interesting thing to monitor as it progresses.

Being political

VG: So you’re really painting about changes.

AH: Yep. To paint changes, the unforeseen changes and the sometimes irreversible changes. I’m also painting about the fact that, the underlying, the common denominator being that whatever we vote for a government like the Howard government, and while ever they are allowed to reign for a certain term, then what that says is that mainstream Australia doesn’t care jack about Aboriginal people. Because when you’ve got the conspiracy that is the Howard government, who I believe are systematically contributing to the ultimate demise of Indigenous culture on the continent, then there’s no hope while a wider community – I should say whiter community – vote that government in. Because the changes can only happen when we have a more egalitarian society, and the Howard government aren’t egalitarian.

VG: So you see Australian society as a very materialistic society?

AH: Yep.

VG: That is, it is still pioneering, it’s still about getting what you can out of the place, and ripping off and leaving. To me this is so evident, this deep understanding is there in your art.

AH: Yep. The art is just – it’s so obvious that that’s just there, and that’s what I’m trying to paint. Well, we know about the issues now. If you don’t know about the issues then chop your head off and go and jump in the river, because it’s like the issues are now available online, the issues are available through public forums that happen, and are snowballing each year because of things that surround NAIDOC celebrations and Indigenous health, and Indigenous art forms and so forth. So the issues are there to be investigated and researched, and understood, so the way I see it is that material society in Australia will implode, and it’s a matter of time.

You see the prime, the archetypal examples, and I’m speaking about the community where I come from, Penrith. It recently boasted it has the highest disposable income per capita in any growing city in Australia , and it also boasts one of the highest obesity rates. So, it’s a matter of time before they put two and two together, and the place implodes, you know.

VG: Does it have the greatest number of fast food outlets?

AH: It does. That’s why they put the first Krispy Kreme donut franchise in Penrith.

VG: Oh gosh. So sad.

AH: And people lined up, people lined up for days. I know people in Sydney who are from corporate firms who send somebody in a cab to Penrith to get Krispy Kreme donuts for their coffee break. How disgusting is that?

VG: Have you ever tried one?

AH: Never.

VG: I have. It’s just pure fat and sugar mixed. The carbohydrate is just there to hold it all together. (Laughters)

AH: Yeah, true.

VG: They’re very soft and very.

AH: Yep.

VG: And very dangerous. So you’re characterising your work as highly political, and really drawing out all of the negative aspects of colonisation.

AH: Hmmm. And trying to put them, expose them, under a magnifying glass.

The more you do it, the less things seem to change. Actually some of my colleagues say that they’re sick of seeing the issues, the same issues in the painting: “We’re sick of seeing it. I think you’re going to shoot yourself in the foot. Why do you keep painting them?” Because nothing’s being done. It was eighteen years ago that Yothu Yindi sang about treaty – that hit song “Treaty” eighteen years ago – are we any closer to a treaty?

There were mixed reactions even from Indigenous communities about the success of a treaty, given that it can implement a divide and conquer amongst Indigenous people. But, I think, the treaty needs to be put on the national agenda, an annual agenda – for more input, that’s all. If that happened over three years, five years, we’d be much closer to a decision over whether we’d implement a treaty or not.

VG: So do you think a treaty might actually start saving some of those landscapes so obviously decimated in your paintings?

AH: Yeah, for sure. For sure. A treaty – the first thing I think of in having a treaty is greater governance to Indigenous people, and a greater governance over individual land, individual country.

VG: Yes, so more opportunity for custodianship.

AH: Hmmm.

VG: Which is an interesting thing that’s developed out of native title. I mean, over all, native title has been quite unsatisfactory for most people, but it can offer the opportunity, even if people can’t claim land, straight out, it can offer them the opportunity to be part of the negotiations around custodianship of land. And quite a few Aboriginal groups, it seems, are happy with that. To still be able to have the links and still be able to visit, camp; sing, but not necessarily to own the land in the white sense of owning it, freehold title.

AH: Sure. It’s difficult to say whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing – a positive or a negative – because what you find with the reason for the abolition of ATSIC was the quick way out – the government didn’t afford the time to run an enquiry about the misappropriation of funding amongst individual groups. When you consider how short a period of time the country’s history – 219 years – it took to arrive at this abhorrent state of Indigenous health and social issues, you would think that the government would invest as long as it took – be it 3 to 5 years – creating an enquiry into how best to advise Indigenous governance of, and dispersion of monies in the community. But the quick way out was to abolish it, and then form the National Indigenous Council, who many of us label the ‘Rubber Stamp Mob’.

VG: Well, certainly the National Indigenous Council doesn’t have a budget, can’t run programs.

AH: Also called ‘silver polishers’, people who just, you know, have the little black boy to bring out the tea and scones or something. It’s just, it’s a – yeah, it’s something that I don’t subscribe to, and something I’m concerned about in terms of representation of peoples on a broad scale. We saw problems arise with individual groups under the, under the banner of ATSIC. Individual groups grabbing and taking, and looking after own mobs. Now, that’s what the media, the whole national media targeted, and exposed. But that’s just government in general. That happens amongst federal government – Mal Colston, you know, have a look at the people who screwed people over in federal government as well.

But it’s ultimately, it’s the condescending comment that Aboriginal people can’t manage money. When people grab and take the money they can and run with it, then you can’t blame people for doing that. Because many people are thinking ‘This is the last chance that my mob have got to see any successful way of life’ and if that comes through the grabbing of money, and running with it, then considering the way capitalism works on a global scale, it’s no different to any other place on the planet.

Being a black man

VG: I must say, you’re reminding me that all this media attention now on sexual abuse and domestic violence in Aboriginal community, creates the idea that Indigenous people have got some kind of greater involvement in these activities than the general population. I just wonder in relation to that: how do you feel as an Aboriginal man, with all of the media attention at the moment on sexual abuse and domestic violence in Aboriginal communities?

AH: The positive outcomes many people wish to see is the eradication of it. And yes, it is rife amongst many remote communities. The problem is that the media attention, when targeting Indigenous issues, rarely resolves a problem but rather is fodder for the boneheads of society, sitting round the barbecues on the weekend getting pissed themselves, and it gives them something to bitch about – about the blacks being irresponsible.

VG: So you’re saying it feeds into that white racism.

AH: Of course, it just fuels it. It just fuels the rednecks of society. And I can speak first hand of that because the predominant population of those people I mention are actually from my community where I grew up. So I’ve burnt many bridges in personal relationships with people that I have previously been quite close to in my adolescence and so forth.

VG: So, you underwent a kind of a consciousness change, when you understood your family background.

AH: Yes, absolutely.

VG: And you pursued an entirely different life course.

AH: Certainly. Perhaps not entirely a life course, but certainly a different thought process. An entirely different thought process.

VG: So your consciousness changed.

AH: Yeah.

VG: Your understanding of race relations and so on. Were you the victim of racist abuse when you were a child? You’ve got a bit of colour.

AH: No, not myself no, but my father did, and I saw it. I witnessed it. And I never forget the moments. Dad always downplayed it, and swore that it wasn’t actually what it actually was.

VG: People do that. I’ve seen that. But was he shamed by that?

AH: No, but he’s a man that holds things, and when people hold things to themselves, it has a compounding effect on either their physiology or their actual health, and the way they – and the means by which they choose to try and comfort themselves.

And I suppose what has happened to my father is similar to the next blackfella. You know, all those kids who are just trying to live in society and there’s still no real opportunity for them to do that. This is what the media needs to consider when they – the sensitivity of people. The media have a responsibility. But I have heard some encouraging positive stories about the late Kerry Packer and certain things that, incidental stories related to him encountering Indigenous folk here and there, if I hadn’t have heard those stories then I certainly would be angry about Kerry of the Packer family. And I’ve always gotten a smile from James over at Bondi too. It’s – until we get widespread Indigenous owned media – as well as Imparja, run by the Central Desert mob.

VG: And Koori Mail?

AH: Yeah.

VG: An Indigenous owned media association?

AH: Until we get media run by Indigenous folk then I don’t think we’ll see a correct balance. And that’s the other thing, in my recently adopted place of residence – which is the inner west in Haberfield, you could go into the local newsagent and you could get Croatian newspaper, you could get Italian newspaper, you could get French newspaper, you could get all this newspaper but you couldn’t get Koori Mail. They say they’d never heard of Koori Mail. And that’s somewhat of a let down considering that someone in Ashfield Municipality has taken the responsibility of actually hanging the Aboriginal flag in the main street next to the Australian and the Italian flag. That was always a proud thing to see every morning coming out onto the street.

Being within an “unforseeable future”

VG: Somebody mentioned to me the prevalence of roads in your work. Someone came into your exhibition and he said ‘I felt like I was walking into “Beneath Clouds”‘.

AH: Yeah. That was certainly a coincidence when that film came out, because I’ve heard that comment before.

VG: Oh have you?

AH: I went to the launch at the Opera House there – of the film – and it was, yeah of course, brilliant – they’ve been coined ‘Adam Hill clouds’. They have become a metaphor for “government”, that is, white, looming overhead, casting an ominous shadow. In later works there are seven, representing five states and two territories.

VG: Ivan Sen’s film “Beneath Clouds” is a highly political film. What I recognised in it is the ongoing dilemma of the young Aboriginal man who is struggling to be good marriage material. This young man battling to make his mark, of being a possible suitor of the young woman, and of ever being able to support his family, or support himself, or to own a car, or to do all those things that others can take for granted. And of course the road. The road is such a major metaphor for life’s journey in the film, and the road is such an important icon in your painting.

AH: It definitely is. It attributes itself to the metaphor of an unforeseeable future. Like a vanishing point. And an unobtainable – our future unobtainable life, all continually out of the grasp of an Indigenous person. The typical livelihood that so many Australians aspire to.

Being a political commentator

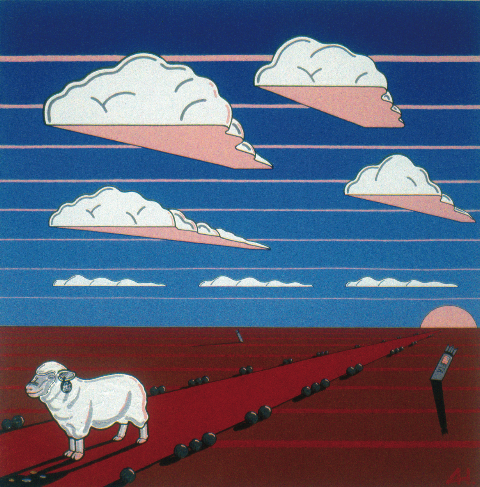

“Leadup to the Federal election”

“Leadup to the Federal election”

VG: And the painting titled “Leadup to the Federal Election”, what made you put a sheep there?

AH: Well that particular image, called “Flocking to the Polls” was painted for a residency during a NAIDOC week at the Australian Catholic University in Strathfield, a few years back. That was specifically influenced by the election at the time in 2004 – and the sheep is representative of the wider community, who just seemingly flock to the polls and just cast a vote because of who their parents have told them to vote for. Or, worst-case scenario you, might hear the comments at the local RSL – ‘Well, I quite like that Tony Abbott because he’s a very handsome man.’ And people cast votes because of this. You know, and Brogden the racist arsehole, making comments like that, and I wanted to represent that mentality, of people just flowing into the polling booths.

I stylised that sheep into a plastic deposit box for the Liberal Party ala the guide dogs at the shopping centre. So it’s got a coin slot on its snout, and it’s a donation box for the Liberal Party, lead up to the election. In the background of that image are a couple of unexploded bombs with a US flag on them and an acronym FTA – which is Free Trade Agreement – which is ultimately what the Free Trade Agreement is about.

VG: Yes, it’s quite a scenario isn’t it?

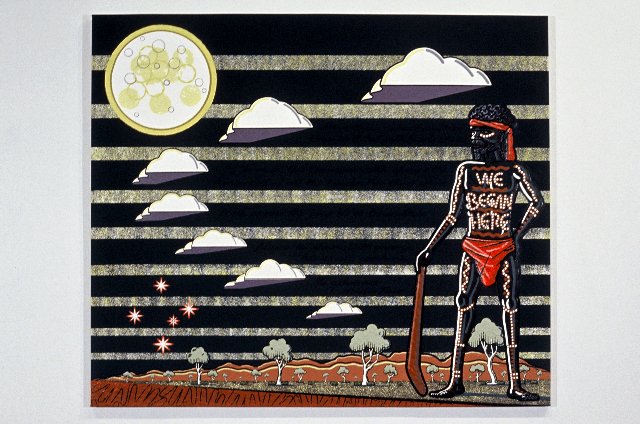

Being an anti-racist patriot: “We began here”

“The southern toss”

VG: And there are other images in your paintings I wanted to ask you to elaborate on. The “Southern Toss” – the painting with the Aboriginal man all painted up?

AH: Yeah. I got a bit of very juicy exposure in the Spectrum on the weekend, in the arts section. One of the journalists wrote a very complimentary little blurb in the feature section. And she’s nailed it on the head, in where I was coming from with that image, and just questioning sovereignty and patriotism to the Australian flag, and the national anthem by the wider community. Once again, it all links back to having a gross misunderstanding and ignorance to the plight of Indigenous people.

And, it’s something that – that image there – I was very angered by the uprising out at Cronulla between the Lebanese fellas and the bogans, and when I saw the bogan filmed, captured on the front page of the Sydney Morning Herald and he had written – or somebody had written for him – on his chest, “We grew here, you flew here.”

That’s when I immediately hit the internet and emailed, and broadcast my thoughts saying that, first of all, nobody acknowledged that it was Gwiyagal Aboriginal country that this all took place on, and total disrespect to the original occupants of the land, and for the bogans to say that this is our turf and that we were here first, a pretty much redneck attitude, but if you trace it back it was actually your forebears who wiped out the Gwiyagal people, and they were there before you, so, you know just think about it.

So I retaliated with that image there, which features the Anangu , this Aboriginal fella with the stylised body paint on his chest that says “We began here.”

Being a critic of Australian whiteness: “an uneasy feeling”

VG: What does whiteness in Australia represent for you? How do you see whiteness here in this country? Is it those people at Cronulla?

AH: Absolutely. The beer drinking, gambling, chauvinistic, sexist, elitist male that is responsible for the promotion of whiteness. It’s people that don’t know anything other than their, literally, their own backyard. Who can’t see past the end of their own nose. It’s people who have an intolerance for anyone that – anyone else that’s not white so to speak. It’s the monocultured vein of society that’s quickly becoming – somehow remaining the majority of society. The unfortunate thing is that in terms of population growth – the equal numbers, or the fast approaching equal numbers of society that can actually also be verging towards an equal majority, that is, Chinese population, Greek population, Italian population – the population that are increasing from those communities, they have a responsibility also to familiarise with the hardships of Indigenous peoples who are continually remaining a minority of society.

So what I’m saying is that it’s a very uneasy feeling walking a street in a predominant ethnic demographic, and not getting the time of day, not having those communities actually celebrate their cultural celebrations without aligning with the Aboriginal flag, without recognising that it’s Aboriginal country. Sometimes I feel that, just in the most severe political climate attending to Indigenous social issues, sometimes you look to people who have a strong culture, that is, visitors from other shores who have now built a strong society here, you look to those people for back up. That’s often the way I feel. Anybody who has a strong cultural background will always, should always be able to empathise greater with the Indigenous plight, as opposed to the non-cultural background of Anglo-Australia.

VG: But are some of those people trying to be white? Are they aspiring to be white as well, in some sections of those communities?

AH: I wouldn’t go so far as to say that, but I would certainly say that there needs to be some sort of allegiance with white government here for those people to reach any form of prosperity in this country. Which Chinese do so cleverly, and have done cleverly. Same with Italians.

VG: Yes. There’s a big historical connection between Chinese and Aboriginal people. Isn’t there?

AH: Yeah, but I’m not saying that there actually is a respected connection. I’m saying that there’s a separation because of economic growth.

VG: So people get very concerned about standards of living, and materialism in sense and often work upwards towards government, to please government, rather than actually look down.

AH: That’s right.

VG: But there’s some really interesting instances of different migrant groups being supportive of Aboriginal people in the past. You’re probably aware that the Greek community in Melbourne actually contributed funds to the Aboriginal Medical Service before the government did and some people such as Alick Jakomos, had very strong connections.

AH: Of course there are exceptions, and that’s one of the greatest Greek populations in Australia , so that’s an amazing gesture from that community. But, it needs to happen tenfold; it just needs to continue throughout communities in a broader sense throughout the country.

VG: And so, whiteness, you see it as actually being bred in the suburbs?

AH: Yeah, in the lower socio economic areas, where interestingly you’ll tend to find a greater mix of different ethnicities, different ethnic backgrounds, but it doesn’t mean that people interact and that people live together as one. So that’s why I stick my four fingers down my throat and throw up every time they pay homage to Australia Day and “I am, you are, we are Australian”. What a gross contradiction. Shouldn’t be just one Australia Day, it should be Australia Year if we’re all living together in harmonious sense, but that’s not the case.

VG: So you see it as a kind of uneasy nation, and uneasy alliance between different groups.

AH: It’s a false alliance, a façade.

Being a visionary

Whitefellas have these obsessions with building monuments to say that this park was officially launched in 1820 by lord pompous or whoever was the lord mayor at the time. Every park you go into, there’s a statue of someone who screwed the place over, you know what I mean, but do we have a statue of Bennelong? So I’m thinking that I want a statue or a simple plaque saying you are on Gadigal land or Aboriginal land in every park in Australia . That’s one of my projects. Some local councils have come to the party, like in the Blue Mountains now there are signs that say you are now entering Wiradjuri land. But every council has to do it.

-Adam Hill

Deadly Vibe Issue 84 February 2004

VG: Finally, what are your hopes for your work? What do you see your work as an artist might actually achieve?

AH: Yeah, ultimately, to reach a platform where I have an opportunity to speak these issues not only within Australia , but to international forums and the dignitaries abroad. People do visit here with a fantasy vision of Aboriginal Australia, need to be brought up to speed before they travel here. So I’ll personally put my hand up to be that ambassador, to travel to those countries, and to announce the way it really is. And I say that through my heart, I tell it how it is. And it’s only going to get harsher, the imagery as it’s shown to you. I’m going to speak it more and more how it actually is. And if people don’t afford the time to get out into the community, and to actually walk the street and talk to people, then they’re going to be able to come to my exhibitions and see how it actually is.

VG: Fantastic. Thank you, Adam.

Vicki Grieves, Koori, professional academic researcher has research interests in the colonialist/historical constructions of gender and race, Indigenous knowledges and public policy. Publications include in the “history wars” debate

http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/lab/85/grieves.html

and Indigenous wellbeing

http://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/npws.nsf/Content/Indigenous+wellbeing+framework

For more information about Adam Hill and his work, and to contact him see http://www.artsconnect.com.au/adamhill/index.htmhttp://www.vibe.com.au/vibe/corporate/celebrity_vibe/showceleb.asp?id=348

http://arc1gallery.com/index.shtm