With a little over a month to go until the centenary of the failed Gallipoli landings, Australia is already in the Titan’s Grip of Anzac commemoration.

Or perhaps it is better described as a celebration.

And now that the 100th anniversary is well and truly upon us, never has there been a more appropriate time to consider the emphasis that Anzac has earned in Australian consciousness and how it has come to shape our views of the “diggers” who took part in it and other seminal battles of the first world war.

During the four-year centenary of the first world war, Australia will spend at least $300m commemorating its small part, globally speaking, in the conflict rather than considering the wider implications of an international conflagration that killed at least 16 million people.

Parochially, Australia calls its festival “Anzac 100” and it is giving rise to all manner of tacky merchandise, from Anzac biscuits and watches to key rings, alcohol and golf balls, not to mention a flood of questionable books, art, poetry and song.

There will be re-creations, sporting events and concerts. And then there is “Camp Gallipoli”, where you can pay to sleep “under the same stars as the original Anzacs” in a special “authentic” swag ($275 for a single, $375 for a double). All profits will go to Legacy.

But will that be mitigation enough for those of us concerned about the pervasive militarisation of the Australian story and what Camp Gallipoli – with its special commando course for kids – is imparting to our young while our politicians render history servile to contemporary nationalism?

Camp Gallipoli’s website, imbued with the ecclesiastical language that has come to define Anzac, asserts that “the ‘spirit of Anzac’” is in the DNA of every Aussie and Kiwi: mates coming together on one special night to commemorate the deeds of those brave Anzacs 100 years ago, eating great tucker, watching historic footage on huge screens, seeing iconic entertainers live on stage and camping in authentic swags will in itself create history. In addition the dawn service honouring those who have fallen will be something you and your family will never forget … a once-in-a-lifetime event and will take your emotions on a roller coaster as its [sic] blends moving tributes with commemoration. You will learn, sing, eat, drink, laugh, (and cry) but most importantly, you will be together.”

Mateship and unity have long been promoted as the bedrock of the so-called Anzac spirit. Mateship and unity of the predominantly white, male variety, that is.

Little wonder, then, that the cherished acronym has at times been misappropriated for exclusionary purposes; consider the 2005 Cronulla riots, where a beach, the Australian flag and the invocation of “Anzac” became pervasive cultural symbols.

“This is what our grandfathers fought for, to protect this, so we can enjoy it, and we don’t need these Lebanese or wogs to take it away from us,” one rioter said, echoing many others.

But the keepers of the Anglo-Australian myth, not least the Australian War Memorial, have gradually been bringing some colour into the Anzac story, slowly dedicating resources to recounting the war experiences of Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander personnel especially from the first and second world wars.

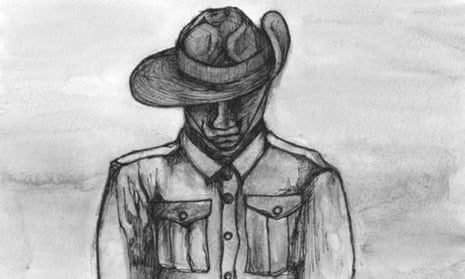

In 2014 “black diggers” were the subject of a play of the same name by Wesley Enoch; the annual National Aboriginal and Islanders Observance Day Committee (Naidoc) Week commemorated Indigenous warriors who’d fought to protect their lands after invasion in 1788 and occupation, and under the imperial banner in the world wars, with the theme Serving Country, Centenary & Beyond.

Just before last Anzac Day, meanwhile, the Sydney street artist Hego pasted a nine-metre-tall mural of an Indigenous first world war serviceman at the entrance to the Block in Redfern, one of the most culturally significant Indigenous plots of urban Sydney.

By conservative estimate 400 to 1,000 Indigenous men joined the 1st Australian Imperial Force between 1914 and 1918. They did so contrary to rules stipulating that volunteers must prove that they were of “substantially European descent”.

Immediately after war’s declaration in late 1914 this was especially problematic for would-be Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander volunteers. But amid mounting Australian casualties (especially after the AIF slaughter at Gallipoli and the European western front) the recruiters became increasingly colour blind.

Some black men tried to sign up numerous times before they succeeded. Others told white lies, insisting that one or both parents were of European stock and their swarthiness was inherited from a single grandparent.

In late 1917 the regulations were amended to state: “Half-castes may be enlisted … provided that the examining medical officers are satisfied that one of the parents is of European origin.”

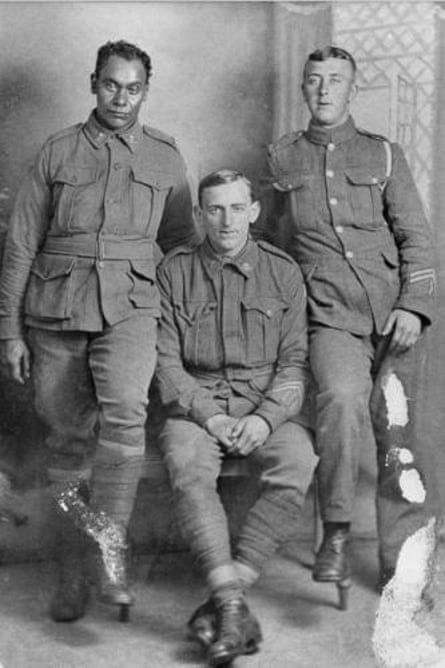

The white lies continued as more and more black men joined. The sepia unit photographs of the infantry, light horse and other corps illustrate the story: every now and then the ranks are punctuated by a black face.

Aboriginality was as impossible to hide as it was deemed irrelevant once a man had volunteered and fought – a profound irony, given that Indigenous people were not properly counted as citizens until 1967 and were regarded until then, officially at least, among the continental flora and fauna.

In her book Ngarrindjeri Anzacs, Doreen Kartinyeri considered 21 men (including Trooper Alfred Cameron junior, the subject of Hego’s Redfern mural) from the Raukkan mission and the lower Murray who enlisted and fought.

The 21, she said, comprised about 20% of the district’s Indigenous men of enlistment age. This compared with an enlistment rate of about 9% for the general, eligible male community.

Five of the 21 died. Kartinyeri wrote:

I find it difficult to understand how so many Aboriginal men were allowed to enlist in the army, as they were not allowed to vote in federal and state elections and they were not counted as human beings. Why did the government want them to enlist? Was it because they did not care who went to fight the war for them? I feel strongly that the protector of Aborigines should have stepped in and stopped them from enlisting. When I look back over the history of my people, I see the [Aboriginal] protector interfering in all aspects of Aboriginal people’s lives, most of the time for no good reason. And yet here they had a good reason but did nothing to stop the men enlisting. My mother and her family always blamed the protector for the deaths.”

To my mind Kartinyeri comes close to the central paradox about Indigenous servicemen – particularly those of the first world war whose antecedents just two or three generations earlier would have experienced first white contact and all of its associated violence, dispossession and injustice.

On the face of it the black diggers of the first world war were fighting for an empire that had invaded their country, killed their relatives and stolen their land. They fought for all sorts of reasons: because their mates had signed up; because of the offer of steady pay and to travel.

Many talked then – as this year’s Naidoc Week highlighted – about the unique Indigenous significance of fighting for “country” rather than empire. For some who fought, this paradox was profound. Perhaps never more so than for Private Douglas Grant.

The pervasive Australian story about “black diggers”, as told by the War Memorial and largely confirmed in the oral and written histories of the black servicemen themselves, is that “once in the AIF, they were treated as equals. They were paid the same as other soldiers and generally accepted without prejudice.”

Demobilisation after the armistice in 1918, however, often brought a cruel return to prewar life for Indigenous soldiers. Some returned to Australia to find that family land had been carved up to provide soldier settlement blocks for white veterans. Others, who’d sent money home from the front, discovered that venal protectors had stolen it and that their families, unable to support themselves in their absence, had been broken up and the children taken to orphanages. Most were not paid their postwar entitlements and were denied the repatriation health services – if injured – that were available to other veterans.

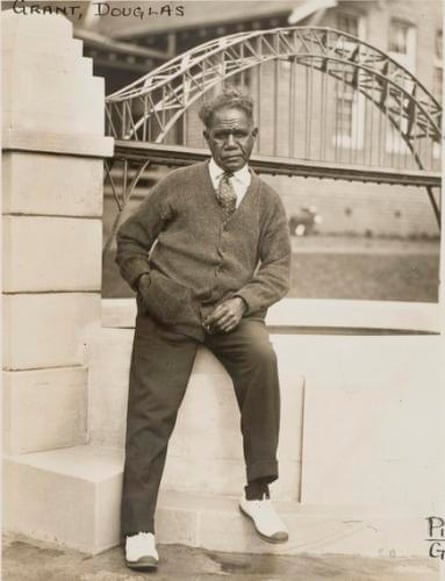

While Grant is today held up as something of an exemplar of the Indigenous experience in the first world war, in many ways what he went through was atypical; a series of remarkable events from early childhood until his postwar return to Australia meant that skin colour really only became a defining facet of his life during the war. Grant is fascinating – and anything but representative.

The story of Douglas Grant

Douglas Grant was born in the bush around Queensland’s Bellenden Ker range in about 1885. His people, the Ngadjonji, had been in constant conflict with pastoralists, miners, police and black trackers as the colonial frontier expanded. According to both the Australian Dictionary of Biography and the war memorial, Grant’s natural parents were killed in a tribal fight when he was about two. But other credible accounts suggest they met more sinister deaths.

In The Embarrassing Australian, a biography of Reg Saunders, an Indigenous Australian who fought in the second world war, Harry Gordon recounts that “several white traders had been killed by blacks” in Ngadjonji country: black troopers employed by the police had arrived, and they were busy extracting as much retribution as they could from the families of the natives who had been concerned in the fight. One of the troopers had actually picked up a two-year-old boy by the ankles, and was about to belt his head into the trunk of a tree. But according to Gordon, a Scottish-born zoologist, Robert Grant, and his wife, Elizabeth, who were on an expedition to collect birds for the Australian Museum in Sydney, “dragged the youngster from his hands”.

For a few days Grant and his wife cared for the boy, until he was carried out of their camp one night by his sister – a girl aged about seven. Next day Grant tracked them down, both cowering terrified in a hollow log. The girl ran away almost as soon as she had been given a meal and the Grants promptly decided to take the boy back to Sydney with them.

In the Townsville Bulletin many years later, Fred G Brown, a former miner, recounted in vivid detail his participation in a reprisal massacre (he refers, typically for a frontiersman involved in the murder of black people, to the killings as “dispersal”) of the tribe believed responsible for the murder of a European goldminer:

Whilst this was going on there were shots and yells all round. In a few minutes quietness reigned and we all collected and found our live number had increased by two gins who had been captured by the trackers and a boy of about five or six years of age. The gins were not a bit upset but the little fellow was very frightened. The little boy we had captured seemed to know I was protecting him. Sucking his thumb he edged towards me and away from the others, eventually getting right alongside of me and in fact scarcely left my side during the next two or three days that we roamed the scrub. During which time, I may say, there were no more dispersals. That kiddy afterwards became Douglas Grant. After several days with the boy, Brown heard that Robert Grant’s expedition was nearby and that ‘Mrs Grant … remarked she would like to get a little black boy … In leaving him with her I knew that he would be well looked after. She looked a motherly kind.’ The Grants fostered the boy who’d been known to his Ngadjonji people (according to popular contemporary accounts of his life) as ‘Poppin Jerri’.”

Notwithstanding the overall accuracy of Gordon’s account of these frontier killings, Brown tells a story that was common on the colonial front line: of white frontiersmen – often miners or pastoralists, accompanied by black police – massacring adult black people and taking their children as curios. While the Grants have mentioned general conflict with local tribes in field notes and reports, their encounters with the locals were peaceful. It seems unlikely Robert and Elizabeth were present for the massacre of Poppin Jerri’s parents or that he was placed directly into Robert’s arms by a black tracker.

As Douglas Grant, the boy grew up much loved and nurtured in comfortable middle-class surroundings in Lithgow and then Sydney, where he attended Scots College as an above-average student. Grant, the first Aboriginal student at Scots, where he became a piper, appears in a 1902 school photograph of the pipes and drums band.

He spoke, like his adoptive father, with a thick Scottish burr was an accomplished visual artist (in 1897 during Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee exhibition he won a prize with the coloured drawing of a bust of the monarch) and had a fine singing voice. He loved classical British literature, not least Shakespeare, and became an avid fan of the popular Australian bush bards Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson, often reciting their work and, inspired by it, even writing some ballads of his own.

After school Grant capitalised on his artistic talents, working as a draughtsman for Mort’s Dock & Engineering Company in Sydney, before becoming a wool classer at Scone in the New South Wales central highlands. Like his foster father he was also a taxidermist. In that capacity he undertook contract work for several Australian museums. As the fostered son of new white immigrant residents, he was regarded as an Australian citizen (a rarity among Australian Aboriginal people then).

As a young black man raised white, there are signs that he was at times self-conscious about his skin colour, though few suggest that it was the cause of any discrimination before the war. His foster mother recalled:

He was very conscious of being black. Quite often he’d come in and grin after washing his hands … then show me them and say, ‘Ma, I think they’re getting whiter.’ He had a difficult time with girls, of course. He would never have contemplated marrying an Aboriginal woman, and his pride or his principles wouldn’t allow him to become too serious about white girls. There was a girl in Annandale, Sydney, who became terribly fond of him and wanted to marry him – but he wouldn’t have anything to do with the idea.”

The Australian naturalist Alec Chisholm, editor-in-chief of the Australian Encyclopedia and a contemporary of Robert Grant, said Douglas had never associated with other Indigenous Australians and, despite becoming a wool classer, showed little affinity with the bush: he was certainly no bushman. He was dead scared of snakes and always kept as close to the city as he could.

His was a tragic case of isolation. He considered himself different from Aboriginal people and he was considered different by the whites. He had full citizenship rights and used to get into plenty of arguments about politics. He was a great Labor party man and, whenever there was a political meeting, insisted on having his way. Grant enlisted in the 1st AIF in mid 1916, just as Australian casualties were mounting on the western front (19 July 1916 – when the battle of Fromelles claimed 5500 casualties including more than 2,000 Australians killed and missing – remains the bleakest day in our post-colonial military history).

On 9 September 1916 Rockhampton’s Morning Bulletin reported that Grant had been ready to go a couple of months earlier, when he passed the sergeant’s examination, but at the last moment a government official discovered a regulation preventing an Indigenous person from leaving the country, and, much to his disgust and to that of his comrades – for he was one of the most popular fellows in the company – Grant had to stay behind until last week when the authorities gave the required permission. It was, perhaps, the first time since he had been snatched from his murdered parents that Grant had been the subject of active bureaucratic meddling because of his colour. Grant sailed in August 1917 with the 13th Battalion.

The following May he was wounded in the first battle of Bullecourt. The Germans captured him and he saw out the war in prison camps near Berlin. While other black diggers enjoyed an egalitarian experience in the ranks, as a prisoner of war in Germany Grant’s skin colour defined him. He was separated from the white prisoners and held with the darker-skinned soldiers of the far-flung British empire: the Gurkhas, Indians, black South Africans and swarthier Canadians.

By some accounts Grant objected to this but his German captors prevailed. Eventually the Ngadjonji boy from remote Queensland was elected to become the intermediary between the prisoners and the Red Cross.

In this capacity he made repeated overtures to the Red Cross for appropriate gifts of food (including curry powder for the Indians) for the other dark-skinned prisoners. Grant’s family – including relatives in Scotland – took a close interest in his welfare while he was imprisoned.

Writing to a David Evans who was stationed with Australian medical authorities in France, Hugh Grant of Motherwell, Scotland, enquired of his adoptive nephew:

He is an adopted boy of my cousin Robert Grant of Sydney Museum. He is a native whom he got up country when a tiny tot. I am afraid he will [not cope with] the change of climate very much. He has been well educated and is a draughtsman to trade + from one who has met him he is a good lad. I feel anxious about him.”

Evans replied:

We are very much interested to hear that he is a real Australian, so we must try and take special care of him on that account. I think there are one or two others, but I am not sure.”

Apart from the anxious letters of friends and relations, Grant corresponded regularly on his own account. Writing to a Miss Chomley of the Australian Red Cross in London, Grant asked her to send him an Australian military tunic, a battalion colour patch, a field service hat with chin straps and an Anzac Rising Sun badge:

I am happy to say that I am enjoying perfect health, but as is only natural I long … for home. Could I also get a copy each in book form the poems of Adam Lindsay Gordon, Henry Lawson and Robert Louis Stevenson; or some books of Australian life … something in which to pass away a few leisure moments which are generally filled with that longing for home sweet home far away across the sea, and to read of it in prose, verse or story would help to overcome that longing. Perhaps, madam, you are not aware that I am a native Australian, adopted in infancy and educated by my foster parents whose honoured name I bear [and who] imbued me with their … spirit of love of home, honour and patriotism.”

She replied:

Am so very interested to hear that you are now secretary of the British help committee [of the Red Cross). It must give you a great deal of work, but of course, as an old Scots College boy I feel quite sure you are equal to the occasion. I know that you are a real Australian, as I have heard it from some of your comrades. I used to think that I was, as both my mother and grandmother were born in Australia, which is rather an unusual record, but I am afraid you would only look on me as quite a newcomer.”

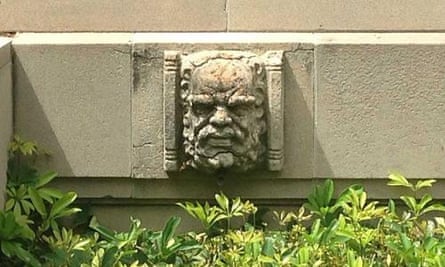

Grant was a celebrity black man – a curiosity, really – among the Germans, too. Doctors and anthropologists measured and photographed his skull (the voodoo science of phrenology, which assumed a person’s character and intelligence could be deciphered from cranial characteristics, still retained some currency in parts of Europe). The noted German sculptor Rudolph Markoeser—who spent the war specialising in “ethnographic sculpture” owing to his access to empire prisoners – modelled a bust of Grant in ivory.

In a later Australian Army Journal article, “Aborigines in the First AIF”, an intelligence corps officer wrote that Grant, “because he was such an unmistakable figure … was given comparative freedom in Berlin late in the war; the reasoning was that it would have been useless for him to try to escape anyway”. The same article quotes a German scientist who met Grant in Berlin and later visited Australia:

I first met the man in 1918 in a south Berlin suburb, while I was working with the Royal Prussian Photographic Commission. Our objective was to collect material on languages, songs and dialects among the Allied prisoners, and of course we regarded Grant as something of a prize. In fact he was not very useful for any study of the Australian Aboriginal; he had been removed from the tribe, and he regarded the natives with almost as much curiosity as we did.”

After the war Grant spent time in England and with his foster parents’ relations in Scotland. He returned to Australia in July 1919 and resumed work with his old employer as a draughtsman. Restless, unwell and beginning to drink heavily, Grant returned to his second childhood home at Lithgow where he worked as a labourer at the small arms factory. During a downturn in 1921 Grant – the only Aboriginal employee – and 12 other war veterans were sacked. Grant picked up other labouring work and devoted much of his energy to promoting the rights of (white) veterans, including via a local radio segment, broadcast through the servicemen’s club. Before alcohol tightened its grip on him, he was also a sought-after speaker around NSW. Literature – Shakespeare – was his favourite subject.

Despite his skill as a taxidermist (his adoptive brother, Henry, eventually took Robert’s job at the museum) he could not find work in that speciality in any Australian collecting institution. It was just one sign, perhaps, of growing estrangement from his foster family. It appears, judging by his later circumstances, that he did not inherit substantially despite outliving both his adoptive parents and his brother. The press of the day indicates that he was becoming increasingly itinerant and alcohol addicted.

“Jimmy Good, a Chinese, of 80 years of age, who resides in Little Bourke Street, Melbourne, was, the other night, walking along that delectable thoroughfare when he saw an Aborigine stretched full length in the gutter,” the Geraldton Guardian reported on its front page in October 1925. Good warned the vagrant against catching cold in the gutter. “The latter came to life very suddenly and smote the good Samaritan on the nose with such violence as to cause him to see a multitude of stars.” The vagrant, Grant, was jailed for assault.

Grant might, as suggested, have been uncomfortable in the company of other Aboriginal people. And he may have retained little connection with the bush. Certainly, all of the descriptions of him by white people sparkle with condescending wonder that an Indigenous Australian man could be so talented and clever. But in the late 1920s, as the trajectory of his personal decline was becoming clear, he took up the black cause. The catalyst for his periodic black activism was apparently the Coniston massacre – the murder of 31 Aboriginal men, women and children in central Australia in 1928. Ironically, a Gallipoli veteran, George Murray – later a police constable – was the unrepentant and ultimately, inevitably, reprieved protagonist.

Grant’s initial writing about the Indigenous lot was partly imbued with the white version of the frontier as a site of benign settlement, despite the murder of his parents and at least tens of thousands more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. He seems to oscillate between a white and a black perspective on issues of invasion, settlement, violence, sovereignty and the general treatment of Indigenous and mixed-race Australians. Ultimately, however, he judges heavily on the side of his own people, and seems, in the end, to have been propelled by conscience and birth. But the piece also brims with love and respect for his adoptive parents.

He begins:

This country was taken without warfare, such as marked the annexation of India, Africa and lesser parts of the Empire. What can we do and what are we doing for the first inhabitants, the rightful owners of this land which was usurped and portioned as your heritage?”

He goes on to talk of post-settlement evil: rape, liquor and disease.

The result of the advent of the European was the sacrilegious breaking of age old customs, laws and dignity, the outcome of war and bloodshed. The native in righteous indignation and wrath fought for the honour of his daughter, wife and family.”

He dedicates considerable attention to the unfortunate plight of the “half caste”, stuck between black and white worlds. He describes the Coniston massacre of Aboriginal people as “damning in the extreme” for what it illustrated about Indigenous rights and wrote at length about the peaceful interactions of his foster parents with the Ngadjonji.

It lies at the footstool of the government, this great crime [Coniston] – against a harmless and inoffensive people, left to their own resources, their land bartered and sold, the spoliation of their only food supply … the kangaroo, wallaby, etc, also the ravishing and rapine of their women folk. If they call for justice they are answered with the lash or the gun … the original inhabitants of the … youngest continent may be found to be the cradle of the world’s people of the present day.”

In the early 1930s Grant returned to Sydney where he took up a clerical job, and permanent residence, at the Callan Park mental hospital. At the same time he was also treated at the army’s rehabilitation facility there. His job at Callan Park seems to have been more an act of charity than a meaningful source of employment. He ran errands and spoke to the patients. But he devoted most of his time and talent to designing and building a war memorial in the hospital grounds – a miniature replica of the Sydney Harbour Bridge arching over a pond. Grant was lonely, isolated and so frequently drunk that the authorities at Callan Park rationed his meagre pay so that it could only be spent on public transport. He counted as a friend Henry Lawson, whom he much admired; Grant would visit Lawson during the latter’s final years and talk endlessly about the war and his time in prison outside Berlin as a black-skinned oddity.

Australian War Memorial resistance to Indigenous commemoration

In recent years, the Australian War Memorial has come under increasing pressure to reflect in its galleries the bloody conflict across the Australian pastoral frontier between soldiers, pastoralists, miners, militias and Indigenous warriors protecting their land after white invasion and settlement. But the memorial, under its director, Brendan Nelson, remains as intransigent on the matter as it does about the erection of an onsite monument specifically to honour Indigenous Australians who fought in the imperial forces. Instead Nelson has commissioned work on a monument depicting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander personnel serving alongside non-Indigenous colleagues.

Meanwhile Nelson’s Indigenous liaison officer, Gary Oakley, is pushing for a separate monument, dedicated specifically to Indigenous Australian personnel, to be erected close to, but definitely not on, memorial grounds. The two positions may not be anomalous, but they certainly offer a confusing testimony to the fraught politics of commemoration, not least in relation to black servicemen and frontier war warriors. So, from a long-held memorial position that there should be no official Indigenous monument, there might soon be two. Both would be imperfect: Nelson’s because it would not be dedicated solely to Indigenous personnel, the other because it would be sited outside the memorial when it might just as easily be within.

A solution would be to commission Hego to adorn a wall at the memorial with a replica mural. It could be done for a few thousand dollars – small change, really, given the $300m-plus Australia is spending on commemorating “Anzac 100” and the $32m spent on the memorial’s new galleries. Amid this profligacy, in an era of purported “budget emergency”, it is clear the memorial’s intransigence on Indigenous matters has always been about ideology, not money.

“The Australian War Memorial is a place where we treat all service people equally and that is reflected in the way the memorial commemorates the commitment and sacrifice of all servicemen and women,” a spokesman, quoting Nelson, told me last year. But Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were no more genuinely equal when they wore a uniform during the two world wars than they were before or after.

And pitifully little is different today. With the probable single exception of Douglas Grant, they were not considered Australian citizens even while they wore the uniform. They fought for an empire that had taken their land, established a federation that still institutionally discriminates against them, killed their not-too-distant ancestors, under a union flag that symbolised bloody injustice to them. Their experience was definitely unique. The war memorial awkwardly points to the story it tells about Indigenous servicemen when asked about its intransigence on frontier war – even though it will not erect a simple statue to honour the unique experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander personnel.

In 2014, when I asked if Nelson was prepared to soften his opposition to depicting frontier violence, a spokeswoman said the memorial held “a rich collection of material related to Indigenous servicemen and women from the first world war: This includes embarkation information, prisoner of war records, Red Cross files, personal letters, service details, works of art, photographs and medals. We also have a significant project under way – ‘The Guide to Indigenous Service Collections at the Memorial’ will identify Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who served during the first world war and display records and collection material related to their individual service.” This was nothing but a fig leaf, for I hadn’t asked about Indigenous servicemen at all.

Oakley, a former submariner in the Royal Australian Navy, has recounted how a previous war memorial director, Steve Gower, an ex-general, had said to him that he’d “had no problem with Indigenous soldiers. We’re all the same.” Oakley explained: “And I’d go, ‘Yes, we are but we’re not. We join the defence force for different reasons. We are a nation of people who’ve been around for a long time. We are not the same as everybody else. To us everybody else is a foreigner. We are the traditional owners of the land … My service to the nation in the defence force, I see that differently. In my eyes I’m doing this for country. It’s different. It’s a different way of thinking.”

Yes, it is different, indeed, as illustrated by the lives of many black diggers who served, especially in the first world war. Especially Douglas Grant.

Harry Gordon interviewed Roy Kinghorn, a war contemporary of Grant’s, for his book The Embarrassing Australian. Kinghorn said he would see Grant every Anzac Day:

He used to speak Gaelic fluently, and I was always asking him to stop using the wretched language. He used to enjoy himself at the reunions early after the war, but he became a sadder, progressively more dejected figure as each April the 25th went by. One day in the late 40s, I saw him sitting under a tree as the fellows from my old unit were marching into the Domain … I broke out of the ranks and went across to him. ‘What are you doing there?’ I asked. ‘Why aren’t you with your old mates? ‘I’m not wanted any more,’ Grant told me. ‘I don’t want to join in. I don’t belong. I’ve lived long enough.’”

It was about then that Douglas Grant – Poppin Jerri – moved to a modest veterans’ hostel at La Perouse, an Aboriginal settlement on the northern headland of Botany Bay, whose original inhabitants, the Kameygal, can claim continuous precolonial settlement dating back tens of thousands of years. Born black, raised white, Douglas Grant died an Indigenous man at La Perouse in 1951.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion