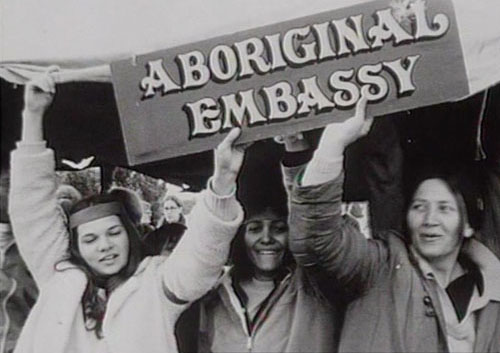

Cheryl Buchanan, Bobbi Sykes and Pat Eatock

more photos

from Cathy Eatock, 6 Feb 2022.

Its been a week since the 50th Anniversary of the Aboriginal Embassy which brought up many memories of my now deceased mother and her recollections of the Embassy, in which she, along with others, were intimately involved. Unfortunately, the shenanigans at the Embassy and the threat of Covid prevented my attendance this year. So in acknowledgement of the significance of the Embassy, the many fighters who were involved and our ongoing assertion of Aboriginal rights and sovereignty, I have documented those herstories below.

A reflection on the Aboriginal Embassy: insights drawn from one of the participants!

The coming of the 50th Anniversary of the Aboriginal Embassy has raised memories of my mother, Pat Eatock, now passed, who was captured defiantly holding the Embassy sign aloft as the canvas structure was once again pulled down. It was a jubilant assertion, that the Embassy, like Aboriginal sovereignty, can never really be removed! I reflect now on being taken to the Embassy as a young child, and the many reminiscences I heard growing up. The assertion of Aboriginal rights in 1972, through the erection of the Tent Embassy, and the brutal response by hundreds of police sent shock waves through the international media and put a spotlight on the appalling conditions of Aboriginal people, with the declaration that Aboriginal people needed an Embassy in their own country.

While it became a movement, we acknowledge those first four young men, Tony Coorey, Bertie Williams, Billy Craigie and Michael Anderson, who following one of the regular political discussion nights hosted by Uncle Chicka Dixon, it was determined to take action to protest the announcement by the then Prime Minister Billy McMahon, influenced, according to Chicka Dixon, by a previous proposal by Jack Patton from 1946 where he suggested setting up an Aboriginal Mission in front of Parliament House. McMahon, on 25 January, had announced fifty-year leases of land to Traditional Owners, where commercial use of those lands could be proved. This was in response to calls for land rights, on the back of the Gurindji Walk-Off at Wave Hill and the Gove Land Rights Case in 1971 where Justice Blackburn’s had rejected Yolgnu claims to their ancestral lands and had determined the Nabalco mine could go ahead. While the leaders of the Sydney Black Power Collective were, according to Gary Foley, set to attend ‘The Action Conference on Racism and Education’ held at the University of Queensland, the four set out to Canberra with Tribune photographer Noel Hazzard driving. It was Tony Coorey who had the insightful strategy to name the umbrella and signs set up in front of Parliament House, an Aboriginal Embassy. It stated to the world that Aboriginal people needed an Embassy in their own lands, while the tent structure reflected the entrenched poverty of Aboriginal people. They soon became aware that the Aboriginal Embassy protest had inadvertently found an anomaly in the law which failed to ban camping on the lands before Parliament House, which fell under federal jurisdiction.

The success of the Aboriginal Embassy was reliant on mob from many nations, who swelled the numbers coming together to defend the Embassy and assertion of our rights to land and our sovereignty. Over the coming days, others became intimately involved, Chicka Dixon, Paul Coe, Gary Foley, Bruce McGuinness, John Newfong, Kevin Gilbert, Sam Watson, Gordon Briscoe, Gary Williams, Dennis Walker, Bob McCleod, Ambrose Golden-Brown and many others. But there were also numerous Aboriginal women, with an Aboriginal women’s conference concurrently held in Canberra, with those attendees attending the Embassy on 28 January 1972. Cheryl Buchanan, Bobbi Sykes, Isobel and Jenny Coe, Mum Shirl (Shirley Smith) and my mother, Pat Eatock, were some of those women.

The issue of land rights was reflected in the Arrernte term Ningla A-Na which Pat had brought with the permission of those Elders while attending a Land Rights Conference in Alice Springs. Ningla A-Na meant ‘we are hungry for our land’, or in the more detailed description Pat was given, ‘We are hungry for our land, as a baby is hungry for the milk of its mother’s breast’. However, significantly the Embassy also protested broader issues than just land rights. The Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and the Australian Government recognised that the term ‘Embassy’ also implied recognition of a sovereign state. On the 5 February, John Newfong distributed a Five-Point Plan, which called for self-governance through a Northern Territory Parliament, Land and mining rights in the Northern Territory, land rights over Aboriginal reserves and settlements, the protection of sacred sites, land rights around and across Capital cities and compensation monies for lands not returnable, with a percentage of gross national income.

Gough Whitlam, leader of the Opposition Labor Party and local Labor Party Member Kep Enderby, attended and spoke to the Embassy protesters on 8 February, with Whitlam endorsing a commitment to delivering land rights. A swath of international guests also visited the Embassy, including Soviet Diplomats, Canadian First Nation representatives and the Irish Republican Army, in addition to members of the general public, unions and other bodies that offered support. My mother recalled that during the cold winter at the Embassy she put her young baby in with a dog with puppies to keep her warm.

Another recollection, she rarely publicly recounted, because it threatened a lengthy jail sentence, occurred before the police first moved on the Aboriginal Embassy. In her efforts to survive after moving to Canberra with the Embassy, and not able at that time to receive payments as a single mother leaving a marriage, Pat had secured a job as a telephonist with the Department of Aboriginal Affairs. However, with the media controversy over Aboriginal policy, Pat was transferred to the quieter Australian Government Printers Office, where she worked on the phone switchboard. It was there, on the morning of 20 July, that she overheard the order come through to urgently print the amended Trespass on Commonwealth Lands Ordinance that would make camping illegal and allow the police to move on the Embassy. Despite the possibility of a charge of treason, Pat immediately feigned feeling sick to go to the nearest phone booth to inform those at the Embassy and to rally the students at the ANU to prepare to fortify their lines. The warning increased the Embassy numbers to a core group of around 30, which then swelled to an estimated 70 with the arrival of students.

However, they were met by a ‘paramilitary force’ of police who forced their way through the interlinked arms defending the fragile canvas frame, topped with the Embassy sign. Peter Burns, a resident and witness, recalled a woman in her fifties being kicked in the groin to break through the defence of the Embassy. The violent images of police beating into the peaceful Aboriginal Embassy protesters were broadcast around the world, covered in the New York Times, The Times London, The Guardian, Le Monde, Le Figaro and Times Magazine. To their credit two ALP Shadow Ministers, Gordon Bryant and Kep Enderby attended in support, with Bryant pulling a policeman off of a protester. Eight people were arrested, with most being bruised and according to Bobbi Sykes, the police injuries related to bruised knuckles.

A Supreme Court challenge was then taken out on 21 July by Pat, Ambrose Golden-Brown, Billy Harrison and Allan Sharpley, with the legal assistance of Terry Higgins, which successfully challenged the ordinance in court. Justice Fox, on the 25th July, found Section 12, having been hastily compiled, was an ‘unsatisfactory piece of legislation’. Pat and other Embassy representatives met with Ralph Hunt, Minister for the Interior, who maintained that the Embassy could not be re-erected, while Peter Howson the Minister for the Environment, Arts and Aborigines, refused to even meet with Embassy representatives. Pat telegrammed Prime Minister McMahon, warning ‘of a national crisis including bloodshed and possibly death’.

Sunday 23 July marked a further escalation when an estimated 200 protesters marched to Parliament House to resurrect the tent Embassy. They again linked arms around the Embassy and chanted “Land Rights Now”, and other slogans. As Pat recalled it, an outer row surrounding the Embassy was made up of Aboriginal women, with the thought that breaking through women would have a greater media impact. However, it was met with an overzealous response, with hundreds of police troops marching row after row, in formation. My mother recalled the brutality of the police, how as the line of police trampled through, she was grabbed by the hair and knocked down, as she fell amongst the legs, sure she’d be crushed if she hit the ground and, in an attempt to retaliate, she bit into the blue uniform and hung on by her teeth. Refusing to let go it held her head above the melee of boots, as the taste of blood seeped through the cloth until someone saw her feet sticking out and pulled her free. It was, according to Gary Foley, ‘one of the most violent confrontations in the history of Canberra’, while Chicka Dixon considered it, ‘the most violent event he had ever witnessed’. The ensuing melee resulted in 9 people requiring medical treatment, including Paul Coe with a cracked rib, eight arrested and five police requiring treatment for bites and abrasions.

Following the second removal by police, Pat, Geraldine Briggs, Shirley Smith and Dennis Walker sought to negotiate with Minister Howson, drafting a letter on 26 July, which called for the dropping of previous charges and offering a commitment by the protesters to erect and then removal of the Embassy if a temporary Aboriginal representation centre were established, with diplomatic status. While Whitlam and Nugget Coombs urged restraint, Minister Howson refused to engage.

On Sunday 29 July, the protesters regrouped with an estimated 2000 participants that marched from the ANU to the then Parliament House, where the tent was re-established, surrounded by three separate rows of interlinked arms, with more defenders jammed between each row. After an afternoon of the police not moving, in a bid to avoid violence, the protesters agreed to allow the tent to be pulled down, allowing only a few officers through. As the tent canvas was removed the protesters were exposed, sitting with their arms outstretched, their hands held high making the peace sign of the times. As the tent was moved away the Embassy sign was retrieved and waved defiantly and jubilantly aloft, confirming though the tent structure may be removed the Embassy and Aboriginal sovereignty itself would always remain.

The Government’s appeal of the previous court finding on the Ordinance was declared on 12 of September by Justice Blackburn, who again determined it had ‘not been notified in accordance with the provisions of the act’. When the Coalition Government then attempted to amend the Ordinance in Parliament to give it legal force, the former Liberal Minister Jim Killen, crossed the floor to vote with the Labor Opposition to prevent the re-gazettal of the Ordinance.

The Embassy and the Governments violent response, broadcast globally, demanded a change in approach by Federal Governments, which had failed to live up to the promise of the 1967 Referendum to address land rights, the entrenched poverty and disempowerment of Aboriginal people. The Embassy likely contributed to the change of government in November 1972, with the election of the Whitlam Labor Government. Gordon Bryant, who had previously intervened against the police onslaught, was instilled as Minister for the new Department of Aboriginal Affairs, with significantly increased funding and the establishment of self-determination as an overarching Aboriginal policy. The National Aboriginal Consultative Committee was established to facilitate Aboriginal decision making in policy direction. The Woodward Commission into Aboriginal Land Rights was established in 1973, with its second report asserting, ‘to deny Aborigines the right to prevent mining on their land was to deny the reality of their Land Rights’. An Aboriginal Loans Commission and the Aboriginal Land Fund Act to purchase land for Aboriginal people were established in 1974. The Racial Discrimination Act (1975) was enacted and Prime Minister Gough Whitlam returned 1250 square miles to the Gurindji people, who had previously walked off of Wave Hill Station demanding the return of their traditional lands. The NT Land Rights Act was enacted in 1976, though legislated under the subsequent Frazer Government, it had been put in train by the Whitlam Labor Government, before its controversial dismissal by the then Governor-General, Sir John Kerr. Though this government retreated from national land rights and withdrew from a commitment to self-determination.

The decades since the Aboriginal Embassy have seen a retreat from self-determination and has moved back to assimilationist approaches, with the mainstreaming of Aboriginal services, combined with repeated cuts to Aboriginal budgets by subsequent conservative governments, which were particularly harsh under the Howard and then Abbott Governments. A punitive policy approach to welfare entitlements was instigated through a series of racially profiled policies with the Northern Territory Intervention, the Community Development Program and the Cashless Debit Card which have racially targeted the removal of the personal agency of Aboriginal people. Despite the Mabo case, land rights remain under pressure and unfulfilled with the forced leasing of Aboriginal lands through the NT Intervention and Stronger Futures legislation and the abject failure of Native Title to provide any controls over traditional lands, which was reinforced with the destruction of the globally significant and sacred, 46,000-year-old Juukan Gorge Caves. These all reflect the lack of Aboriginal decision making, instituted through the abolition of governance structures, with the removal of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission in 2004 after 14 years and then the defunding of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples in 2014 after only five years of operation. In many ways, these policy approaches have marked an attempt by Federal Governments to reverse the impact of the Aboriginal Embassy.

Yet the ongoing legacy of the Aboriginal Embassy is what remains to be done. Achieving justice for Aboriginal people, enacting Australia’s obligations in international law and improving the dire social indicators identified in the Closing the Gap Strategy, all demand that real self-determination is instigated through Aboriginal governance. Aboriginal sovereignty having never been ceded requires a treaty, like the other Commonwealth colonised territories, of Canada, the United States and New Zealand. It requires real national land rights, which also addresses land needs for those in developed and settled urban and regional areas, with compensation and ongoing resources to fund self-governance, services, housing and infrastructure to develop employment initiatives and to respond to Aboriginal community aspirations. The key lesson from the Embassy is that such positive change requires mob and non-Aboriginal people coming together to demand change and a responsive Federal Government with a strong social justice agenda. It requires political will and integrity to establish a Makarrata Commission. It requires a federal Treaty to mark a concerted shift and a departure from contemporary processes of colonisation to an approach based on shared respect, shared resources, and joint sovereignty.

from Cathy Eatock, 6 Feb 2022

It was always said when the Boys left the Embassy and before John Newfong got there, if it was not for Pat Eatock holding everything together, the Embassy would have disintegrated and would not have survived.

It was something I remember them talking about.

Lots of stories. Cliff Foley