William Wentworth had a clear priority when, in February 1968, he became the first federal minister with responsibility for “Aboriginal affairs”.

Toilets.

It was 190 years since European invasion, occupation and all of the violence and dispossession that followed. And it was less than a year since nine in 10 Australians had voted at referendum to give the commonwealth power to legislate for Indigenous Australians and to count them in the census.

And yet, within weeks of being named minister in charge of Aboriginal affairs under prime minister John Gorton, Wentworth determined that he must expeditiously provide thousands of toilets to the Indigenous residents of the Northern Territory deserts.

Observing and listening at close quarters was Barrie Dexter, the head of what was then the office in charge of implementing the commonwealth’s new policies for Indigenous Australians. Dexter was also executive member, along with the brilliant economist Nugget Coombs and the esteemed anthropologist William Stanner, of the Council for Aboriginal Affairs – established by the former prime minister, Harold Holt, after the 1967 referendum to address the appalling legacy of colonisation on Indigenous Australians.

Wentworth was apparently so utterly preoccupied “during 1968 and 1969 with the need, as he saw it, for toilets for Aborigines in the Northern Territory” that he called Dexter to Parliament House “urgently” one day.

Dexter recalls, with a wry literary twinkle in Pandora’s Box, the newly released memoir about his decade from 1967 as Australia’s most senior Indigenous policy-maker: “ ‘Barrie,’ he said as soon as I arrived, ‘it is disgusting that Aborigines are defecating all over the Northern Territory. I want you to build community toilets there, as an urgent project.’

“‘But Minister,’ I replied, because I believed Aborigines needed lots of other things before public toilets ... ”

Dexter “ruminated ... concluding that the office could have no part in giving priority to a project of this sort as a first effort after two centuries of neglect”.

No minister!

Dexter’s book, edited by the academic historian, actor, artist and activist Gary Foley and his research associate Edwina Howell, offers an extraordinary insight into the commonwealth’s policy – and political – responses to the 1967 referendum and to the political class’s early (often bigoted) attitudes towards Indigenous Australians. It covers the rise of Aboriginal activism, including the establishment and violent police move against the Canberra tent embassy in 1972 and the emergence of the “black power” movement to which Foley was central.

Dexter, 93, also a former career diplomat, wrote the 527-page book after he retired from the public service, while a visiting fellow at the Australian National University between 1984 and 1987. He details, with brutal honesty, his service in the pursuit of a better deal for Indigenous Australians under six prime ministers (from Holt to Malcolm Fraser) and a longer list of ministers including William C – “WC” –Wentworth. Dexter’s account is made extraordinary by his meticulous record-keeping; he delves into his extensive correspondence and diaries to detail the political obfuscation, lack of commitment and understanding that too often characterised his service in the pursuit of a better lot for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

He writes eloquently, with a strong sense of humour and an eye for the absurd (it’s clear he applied such traits to his service; had he not, I suspect, he’d have gone mad) about a period of hope that was, however, too often marked by political and bureaucratic apathy and a paucity of empathy, understating of and commitment to improving Indigenous lives. He, Stanner and Coombs were stuck between this lot, which saw him as meddling and often too progressive, and radicals like Foley, who saw him (wrongly) as a contemptible figurehead of political and bureaucratic intransigence and prejudice.

But Dexter was an altruist. He knew he was up against it from the start when Holt asked him to head the council and to “open” the Pandora’s box (of the title) of social, political and historical issues in order to improve Indigenous lives.

He spoke candidly to his political masters in private, often to his detriment. And this is the record of what he did and achieved.

This book is a remarkable historical document. But its backstory is no less extraordinary and, I believe, touching.

In 1972 Dexter, the first head of the Department of Aboriginal affairs, sacked the 22-year-old Foley from his public relations job (“writing their propaganda”, as Foley describes it with typical, gruff candour today). Except to say Foley was on his third warning after six weeks in the department, and that a scuffle with another public servant who had condescended to him was involved, the precise details are excluded here to protect those who can no longer defend themselves.

Foley walked into a life of more heightened activism (which really began when he was expelled from school as a teenager, for no other reason than he was Aboriginal) that soon brought him into conflict with successive governments and, perhaps inevitably, Dexter.

Throughout the 1970s rumours circulated in the press that Black Power had drawn up a list of top 10 assassination targets. Dexter, supposedly on the list, was given a special police guard for two years amid fears for himself and his family. Dexter, meanwhile, had been informing the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (Asio) about his suspicions of a number of black radicals (including Foley). Asio was fearful, at the time, that communists were cultivating black activists to destabilise the state.

Forty years later, while researching his doctoral thesis on Black Power and the tent embassy (for which he won the University of Melbourne’s chancellor’s prize for excellence in 2014), Foley searched his own Asio file under the 30-year access rule. He was angered by the discovery that Dexter had been continually asking for him and others to be investigated.

That was a few years ago. Foley rang Dexter out of the blue. Dexter agreed to meet at his Canberra home.

Foley, now 65, makes it plain he regarded Dexter as a “political enemy” in the 70s and he would have been “happy if Dexter were to drop dead”, but he insists there was never a Black Power hit list.

“I asked him why he thought we would want to kill him,” Foley wrote last year. “That resulted in a lively exchange during which we were able to quickly resolve outstanding differences after I was able to assure him that as much as I disliked him back then, there was never a Black Power death list.”

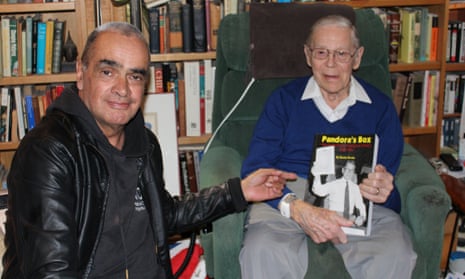

During that meeting, Foley suggested Dexter write a book about his experiences in Indigenous affairs. Dexter said that he had, and that it was in the archive, unpublished, of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in Canberra. Foley immediately determined that it be published and Pandora’s Box is the result of a meticulous edit by himself and Howell.

Foley will launch the book for his old nemesis at the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House, Canberra, on Saturday.

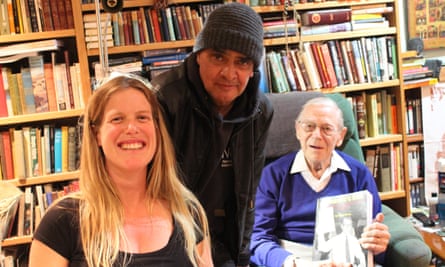

Foley and Howell caught up with Dexter in his Canberra home this week to appraise the book that has been so long coming. On Wednesday evening Foley had been awarded the red ochre prize, Australia’s most prestigious peer-assessed award for an Indigenous artist, in Sydney.

Foley – described by his mate, the novelist and historian Tony Birch, as “one of the true radical figures of both Aboriginal and Australian history” – is a disarmingly, sometimes brutally, plain-speaking man whose strident activism has always been as devoid of public sentimentality as it has of black-white prejudice.

It is deeply moving to see Foley and Dexter together today. Foley is sprightly but with a stick (a “deceptive prop”, Birch reckons) in the vivid autumn of his life, attracting due recognition as a historian, artist and activist. Dexter is physically frail and deaf in his life’s winter, but his mind is nimble and proud with recollections of public service and his achievements (the establishment of a permanent department for Aboriginal affairs and the 1976 Aboriginal Land Rights Act among others), against the odds, in Indigenous affairs.

Foley says: “This book is a testament to the possibility of genuine reconciliation. If me and this guy can reconcile our differences to the extent where I was determined to get this book out and published for him before he died then that’s a fairly significant thing ... Apart from all of the really important stuff in it, its mere existence speaks volumes about what is possible in the way of reconciliation between peoples who 40 years ago were on completely opposite sides of the fence.”

Foley, an associate professor who teaches at Melbourne’s Victoria University, says he was surprised at how little he genuinely disagreed with in Dexter’s manuscript which he regards as “one of the most important historical documents that I’ve seen in my time”.

“I was really surprised that we seem to agree on a wide range of aspects of things that were going on in that era,” he says. “Somehow or other we both seem to have arrived at the same point in our understandings and analysis of that period of history. But, you know, I think both of us have changed a little bit over the years. He might reckon he hasn’t.”

You’ve changed?

“Yes, clearly I have ... I think there was a lack of appreciation on both our parts as to what really each side was up to ... I actually believe if I’d had access to this sort of information that is in this book at that time it may have had a different effect on what was going on. We would not have been as harsh in our judgments and in our things that we tried to put people like Barrie through.”

Asked if he had misjudged Foley by sacking him, Dexter says: “No. It made him.”

Foley laughs and says: “It would’ve been terrible if I’d stayed in the [public service] department. What would I have become? I would’ve become a public servant. Which would’ve been a disaster for my career. So he’s right. It did make me.”

The pair don’t concur on everything. There is agreement on who was the best (Gough Whitlam and Holt) and the worst (William McMahon and Gorton) prime ministers regarding Indigenous affairs. They will not unite on who was the best minister, but seem to agree that Wentworth was almost certainly the worst of the worst.

Dexter regards himself as an optimist when it comes to the future of Indigenous Australians. Foley is more pessimistic.

Dexter says: “If they held a referendum today would it be the same result [as 1967]? I think yes because ... one thing is saying that you ought to give the Aborigines a fair go and the other is seeing the colour of that fair go. Since 67 there’s a much wider knowledge of the maltreatment of them [Indigenous Australians] ... I think you have to accept that while much the same number of Australians would be in favour of doing something, the percentage that know what to do is still much the same as at the time of the referendum.”

Foley disagrees: “Any question today to do with Aborigines I think would have difficulty ... getting up because attitudes have hardened. I mean, I hear what you say about the general Australian thing for a fair go, but with asylum seekers, with Aborigines, attitudes have hardened and there is no way that 90% of the Australian people today would vote yes in a referendum on Aboriginal issues I think. I think there’s been a white backlash since the progressive days of the early 70s and I think that Pauline Hanson ... gave permission to Australian people to be racist. John Howard picked up on many of the ideas or the policies of Pauline Hanson and attitudes have hardened since that period.”

Both men agree, however, that Holt emerges as, perhaps, an unlikely hero – someone with altruistic motives in setting up the council on which Dexter served.

Foley says to Dexter: “One of the things that you say is that Harold Holt was determined to make a difference and I think that’s one of the multitude of important things to come out of this book. Since I’ve read your book I say, ‘Gee, if Harold Holt had not gone swimming maybe Australian history would have been a ... lot different today.’”

Dexter: “Agreed.”

Howell, however, says she believes Holt was responding with political pragmatism as much as altruism to the sentiment expressed in the 1967 referendum.

Foley: “I don’t see politicians of goodwill any more in the landscape. And we all had an opportunity to do great stuff in that period but somehow or other we got foiled. You got foiled. We got foiled.”

In that sense Pandora’s Box can make depressing reading because far too little has changed.

The book, published by the Indigenous Keeaira Press, records how Coombs wrote of Gorton: “Unfortunately Gorton’s image of Australian society, like that of many of his compatriots, had no place for Aborigines as such. He saw no justification or need for special policies to help them, and the idea that Aborigines had valid rights to land based on traditional title was to him wholly unacceptable.”

And there is the bit where Dexter observes how bureaucracy was caught in a damaging myopia that viewed Indigenous advancement through the prism of “major conflict between ... the Aborigines and progress”.

“‘Progress’ in this sense is defined as the plundering of the contents of the soil, the establishment of major modern industries and the introduction of an uncontrolled hotel into areas of Aboriginal Australia where the Aborigines have until now largely lived with some protection ... ,” Dexter wrote.

The more things change ...

Foley leans over Dexter who sits in a chair in his home which is adorned with hundreds of books and the keepsakes of a well-travelled life.

He shakes the old man’s hand once. And again. This time he holds Dexter’s right hand in his and clasps it with is left, too.

Foley says to Dexter: “I’ll see you on Saturday mate. Rest up eh? We’ve been waiting a long time for this.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion