In the Mount Druitt Police Citizens Youth Club, the beating heart of Sydney’s working class western suburbs, Wally Koenig, a 58-year-old former detective and Olympian, watches over a group of young wrestlers. Wrestling is a different world and Koenig speaks the language fluently – snap downs, bridges, duck-unders, cradles. Whistle at the ready, his mind is on the upcoming national championships. “I want nothing but gold medals in Adelaide,” he shouts. “We can do it but we’ve gotta be serious.”

The Mount Druitt PCYC wrestling room is a spartan affair with a spongy mat, benches for parents and large posters, one marking Koenig’s 1988 Seoul Olympics experience, a portal to glory in a faraway land. The others – Mexico, Munich and Istanbul, chart the extraordinary journey of the club’s founding father, the first Aboriginal to wrestle in the Olympics and the man known in these parts as Uncle John.

Uncle John Kinsela, the oldest of 10 children born to a Wiradjuri father and a Jawoyn mother, enters the wrestling room with a big smile, pushing the wheelchair of an old friend. Parents instantly surround him. One mother thanks him for posting tournament videos on Facebook. It’s early evening and he’s full of energy despite being up at 5.30am to work with Koori kids in the Breaking Barriers program. “Boys and girls wrestling together, all cultures mixing,” he says as he surveys the room. “It’s fantastic.”

Koenig takes a break from the training mat to share the history of the club, noting Kinsela’s role as founder and earlier as his mentor. “In my teens John looked like a big man, my first wrestling hero,” he explains. “When I was coming through we were the same weight for a few years and he spent a lot of time sharing the skills and techniques he’d learned overseas. If you look at him now its he’s such a gregarious, fun loving guy – it’s hard to believe he was a gladiator for a big part of his life.”

When Kinsela got too old to run the wrestling classes, Koenig was glad to step in and maintain the tradition. The succession plan worked and the club is thriving: “We’ve never enjoyed this level of talent, including six Australian champions.” says Koenig.

Born in Sydney’s Surry Hills in 1949, Kinsela’s childhood was a story of movement between Aboriginal communities. His sister Lorraine describes it as moving in a “bubble of Aboriginal cousins”. The family finally landed in Redfern and at 14 Kinsela was forced to leave school and provide for his family, working in a sock factory and on a paper run.

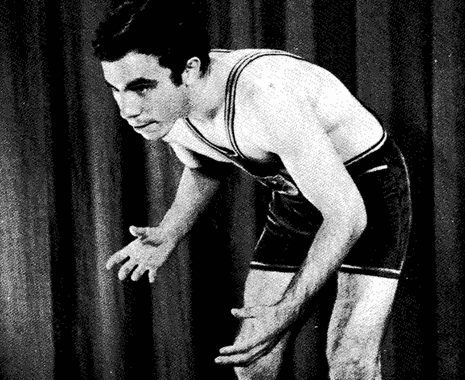

Kinsela didn’t plan to be a wrestler. Like most Kooris he had boxing in the blood and one day his boxing trainer didn’t turn up and the wrestling trainer invited him to the mat. He excelled and made the final of the NSW state titles three months later. “It’s survival of the fittest and so strategic,” recalls Kinsela “You have to outthink and outmanoeuvre.”

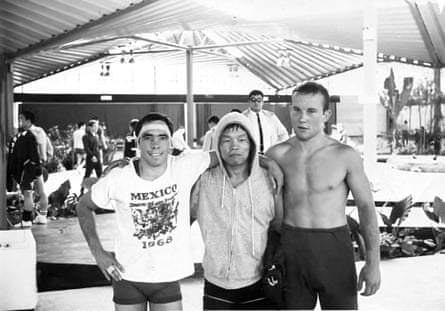

His meteoric rise saw him win the Australian championships and selection for the 1968 Olympics in the 52kg division whilst still only 18. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “It was my first time overseas and we were given 10 weeks in Mexico to acclimatise.”

The Mexico Games were a blur for Kinsela but he remembers thousands of fans at the Olympic Village entrance and for the first time in his life he “felt important”. It was a culture shock and he remembers seeing the Indian wrestlers “walking around holding each others pinkies”.

On the wrestling mat he lost both his matches to Italian Vincenzo Grassi and Soviet champion Nazar Albarian. “These guys were full time professionals,” he says. “It was their job and I was just a part timer but I learnt a lot.”

Not all sports escaped the politics and Kinsela remembers Australian 200 metre silver medallist Peter Norman wearing a human rights badge to support fellow medallists and African Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos in their famous black power salute. Norman was subsequently banned from running for Australia and died a broken man. “It was a rude awakening for me,” says Kinsela. “All Norman did was wear a badge and a simple gesture cost him his career. He was a gentleman, a Salvation Army officer and its so sad what happened to him.”

Following his return from Mexico, Kinsela was called into national service for the Royal Australian Artillery in Vietnam. In 1970, conscripted Gunner John Kinsela flew to Nui Dat in Vietnam and joined 106 Battery, 4th Field Regiment. On his first day he saw Viet Cong bodies piled up and covered in lime. The smell stays with him to this day.

He saw action early but his nerves were shredded and the constant fear of being overrun by the Viet Cong “sent a shiver down my spine and I slept with one eye open”. He experienced no racism and great camaraderie which made him “equally proud to be Australian and Aboriginal”.

Kinsela returned from Vietnam in 1971 suffering from appendicitis and tonsillitis and after a series of operations had five months to prepare for the Munich Olympic trials. He surprised the wrestling community with his fitness after the layoff and was selected as one of only three wrestlers across 10 weight classes.

Kinsela arrived at the 1972 Games a man of the world in contrast to how he was in Mexico. He won his first bout against the Guatemalan, Pedro Pineda, making headlines back home as the only Australian winner on day one. On day three he faced his old nemesis, Grassi, and his progress would be tested. In an epic nine-minute struggle the Italian prevailed by two points – and complimented Kinsela on his improvement.

Kinsela finished seventh in the 52kg division and was on a high but his mood was shattered when he heard the familiar dry crackle of an AK47 machine gun. The horrifying Munich massacre had begun in the Olympic Village, in which Palestinian terrorist group Black September slaughtered 11 Israeli athletes, including four from the wrestling team.

The Games were suspended for the first time in history and Kinsela was devastated by the unfolding events. The Australian wrestling coach Dick Garrard was friends with his Israeli counterparts and the two teams were close, often sharing a sauna to lose weight. Kinsela decided to retire.

He returned to a nation divided over the Vietnam War, which had now swung in favour of Ho Chi Minh’s North Vietnam. Kinsela was heckled in public for wearing his returned services badge and this triggered confusion, resentment and depression in many servicemen, including Kinsela. They were unwelcome at Anzac Day marches and in response he “never mentioned to anyone that I fought in Vietnam and got on with life”.

He married his childhood sweetheart Yvonne in 1972 and was talked out of retirement to wrestle again, making the Australian team for the World Championships in 1974 in Istanbul. He again qualified for the 1976 Montreal Olympics but did not make the final team due to internal politics, retiring for a second and final time.

Missing the structure of military life Kinsela joined the 1st Commando Regiment. Kinsela had always wanted to join the SAS and in 1981 he won the Commando of the Year award scoring 100% in his demolitions exam, one of his proudest achievements. “I beat barristers and policemen,” Kinsela says.

After a six-year stint in the Commandos he returned to work as a courier and with the Aboriginal community. But the jungles of Vietnam have a long reach and Kinsela started to show signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. He felt anxiety and panicked if people were late, became quick tempered and began to binge drink as a coping mechanism. Confused, he lost his bearings and too proud to admit his problem, he “hit the wall”. In 2001 Kinsela suffered a mental breakdown and was admitted to a veteran-friendly institution for treatment.

Kinsela was treated successfully and today is bursting with a sense of mission, no longer dragging the glacier of the past behind him. He has moved from the valley of the shadow to enchanted ground and at 67 he values every day, although pancreatitis and depression still take their toll. “I don’t want anyone feeling sorry for me,” he says. “It just impacts my ability to get around and help.”

He proudly attends Anzac ceremonies and is preparing to speak at the upcoming Indigenous veterans memorial service. His lifelong passion for social justice has found a home as the chairperson of the successful Mt Druitt Circle Sentencing program in which Aboriginal offenders face up to a circle of elders who act as jurors.

“John puts his heart and soul into everything he did,” says sister Lorraine. “He’s still doing it with the kids programs and the court program. He served his country twice, is a dual Olympian, been a great father and husband and survived personal hell. And here he is, resilient, busy, pushing on and helping others.”

His legacy in keeping kids out of jail is matched by his wrestling legacy. He is on the board of Wrestling NSW, does judging and pairing at local competitions and is friends with all the wrestlers on Facebook. Some of his students have stayed in wrestling and contribute as coaches and referees including Shane Parker who kept the Aboriginal wrestling tradition alive at the Delhi Commonwealth Games. “It’s the best club in NSW,” he says of the achievements of this little wrestling room.

Koenig ends the training session with some encouraging words for his young students. “You guys worked like demons, well done.” The kids scatter back to their parents and its time to leave with everybody saying goodbye to Uncle John.

As we head into the night John Kinsela, the first Aboriginal Olympic wrestler and Commando of the Year, who breached the limitations of race and education, reflects on the underlying foundation of his success. “The reason I did so well is that I was nurtured and now I am passing on someone else’s legacy,” he says. “I’m doing things for other people and there’s nothing more important than giving back.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion